When you envision downtown DC, what do you picture? What sounds do you hear? Who is passing you on the street?

In 2019 Apple corporation opened its East Coast flagship store in the historic Carnegie Library at Mount Vernon Square. Located at the intersection of Massachusetts and New York Avenues, Apple becomes the newest corporate entity in Mount Vernon Square and its surrounding neighborhoods. Many people lauded Apple’s renovation of this historic structure. Few, however, commented on the neighborhoods that had been lost to make way for this wave of development.

Since 1840, DC’s downtown communities endured a pattern of displacement initiated by real estate developers, corporations, and government officials’ efforts to “renew,” AKA gentrify the area.

As you explore the ways Mount Vernon Square changed over almost two centuries, consider your own experience with the neighborhood. What has been lost to make way for what you see today?

Workingclass Mt. Vernon Square 1840-1870

Origins and Development of Mount Vernon Square

Although Pierre L’Enfant’s original 1792 plan for DC included Mount Vernon Square, it remained undeveloped until October 1840. To serve a growing residential population, Northern Liberties Fire Company constructed a firehouse. As the community continued to expand, President James K. Polk authorized the building of Northern Liberty Market in March 1846. A center of daily life, the market served the population of Mount Vernon Square.

By the mid-19th century, the area had become a predominantly immigrant and African American, working-class neighborhood.

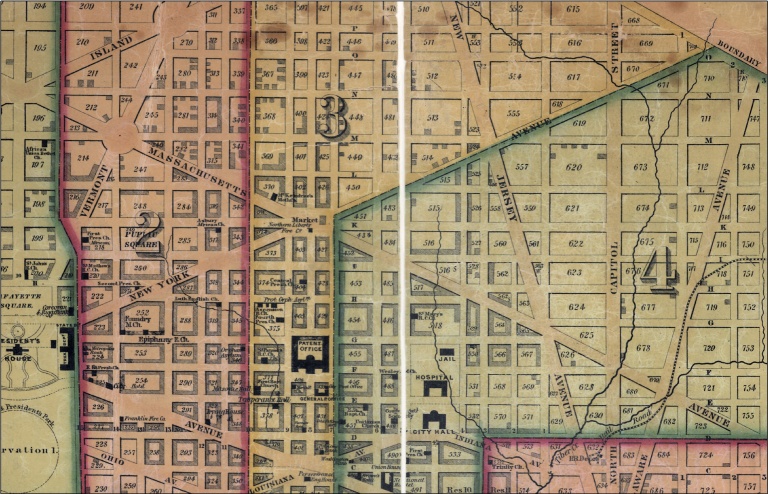

Keily’s 1851 Map of Washington, DC shows the location of the Northern Liberties Fire Company Northern Liberty Market within Mount Vernon Square.

Courtesy of Open Data DC.

Know Nothing Riot and Disruption in Mount Vernon Square

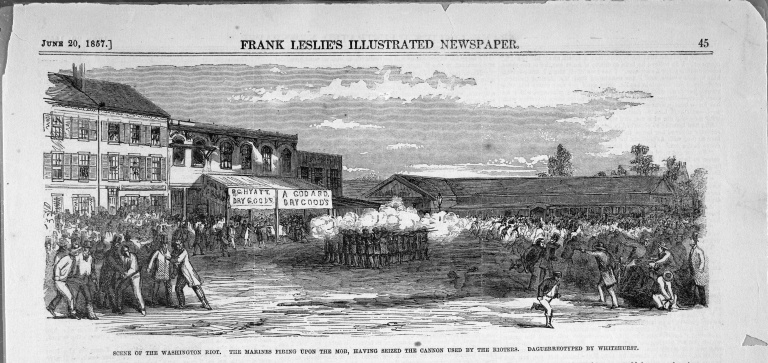

During a local election on June 1, 1857, violence erupted at Northern Liberty Market when Baltimore street gangs disrupted polling locations. The gangs were hired by the Know-Nothing Party, or American Party, a political group known for its anti-immigrant agenda. Mount Vernon Square’s working class, racially mixed, immigrant population made it a prime target for the violent acts of voter suppression often used by the Know-Nothings to ensure their party’s election success.

President James Buchanan reacted swiftly, dispatching 110 marines to protect the polls. Although troops were summoned to combat the gangs, community members paid with their lives. According to eyewitness accounts, rocks were thrown at the marines who responded by firing into the crowd. Six were killed and twenty-one were injured.

Marines fire into crowd on June 1, 1857 killing 6 and wounding 21. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Know Nothing Riot.

Courtesy of the Historical Society of Washington, DC

Displacement, Destruction and Tragedy at Northern Liberty Market

The city government passed a bill authorizing the destruction of Northern Liberty Market in June 1872. Although a portion of the population petitioned for the closure, citing poor sanitation and “a most disagreeable stench,” many vendors and patrons vehemently protested.

In an effort to suppress further protest, Board of Public Works Commissioner, Alexander R. Shepard, ordered a crew to raze the market in the dead of night on September 4, 1872. In the midst of demolition, tragedy struck. A wall unexpectedly buckled, killing 40-year-old John Widmyer and 15-year-old Millard Bates. At the time of the collapse, Widmyer, a butcher at the market, was removing some final hooks from his stall while Bates hunted rats in the debris. Workers dug for fifteen minutes to reach their bodies. Sadly, they found the pair “crushed quite terribly.”

Upscaling Mt. Vernon Square 1870-1910

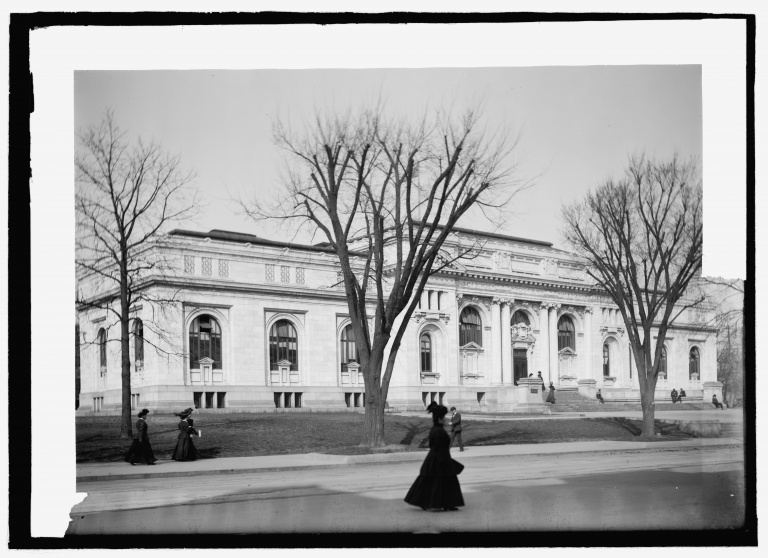

From Park to Library: Changing Public Spaces

Upon the destruction of Liberty Market, Mount Vernon Square was transformed into a park for the community, creating additional green space for city residents. Developers lined the square with new homes and wealthy, white Washingtonians moved into them, transforming the neighborhood. As the area became an upscale neighborhood, Andrew Carnegie provided funding to build a library in Mount Vernon Square. Carnegie donated money across the country to build numerous libraries. Some citizens opposed the library’s construction and wanted to keep their community park. However, city officials believed receiving a coveted “Carnegie Library” would confirm the high status of their city and solidify the transformation of the neighborhood.

The 1902 image of the construction of the library looks southwest towards 7th Street and K Street Northwest. The image is one of the few sources documenting the workers who built the library. Hahns Shoes in the background was an anchor of the 7th Street shopping district.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Philanthropy and Class Struggle

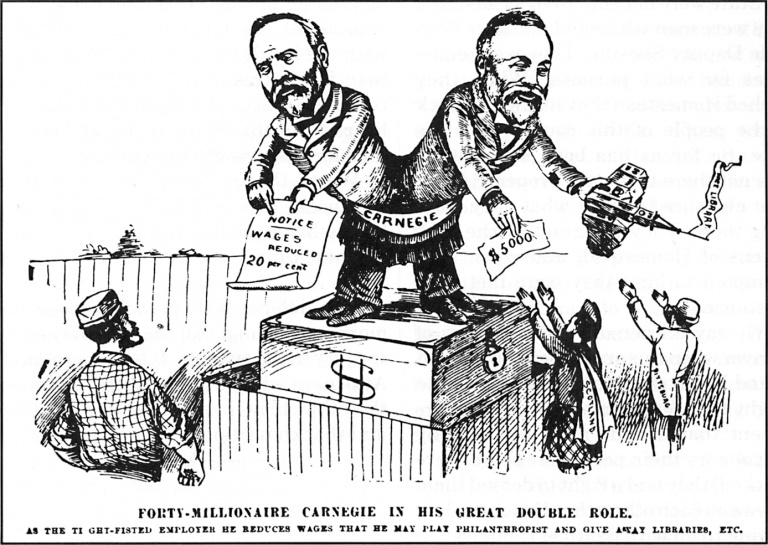

Many of his contemporaries viewed the money Carnegie donated to build libraries as blood money. With his philanthropy, Andrew Carnegie sought to counteract the negative publicity he received following what became known as the Homestead Massacre.

In 1892, workers from the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers went on strike at the Homestead Steel Works outside of Pittsburgh to protest wage cuts. The labor struggle escalated as Carnegie brought in armed guards to protect strike breakers. A pitched gun battle ensued that left at least sixteen people dead and hundreds more wounded. The Pennsylvania governor sent in the state militia to restore control of the mill to the Carnegie Corporation, which brought in strike breakers and broke the union. While the Homestead strike was a labor victory for the Carnegie corporation, it proved devastating to Andrew Carnegie’s reputation.

The Saturday Globe of Utica, NY, produced this political cartoon to exemplify the dual nature of Carnegie’s management of his money. His perceived generosity directly opposed his harsh treatment of workers in the name of profit.

Courtesy of the American Social History Project.

Early Days at the Carnegie Library

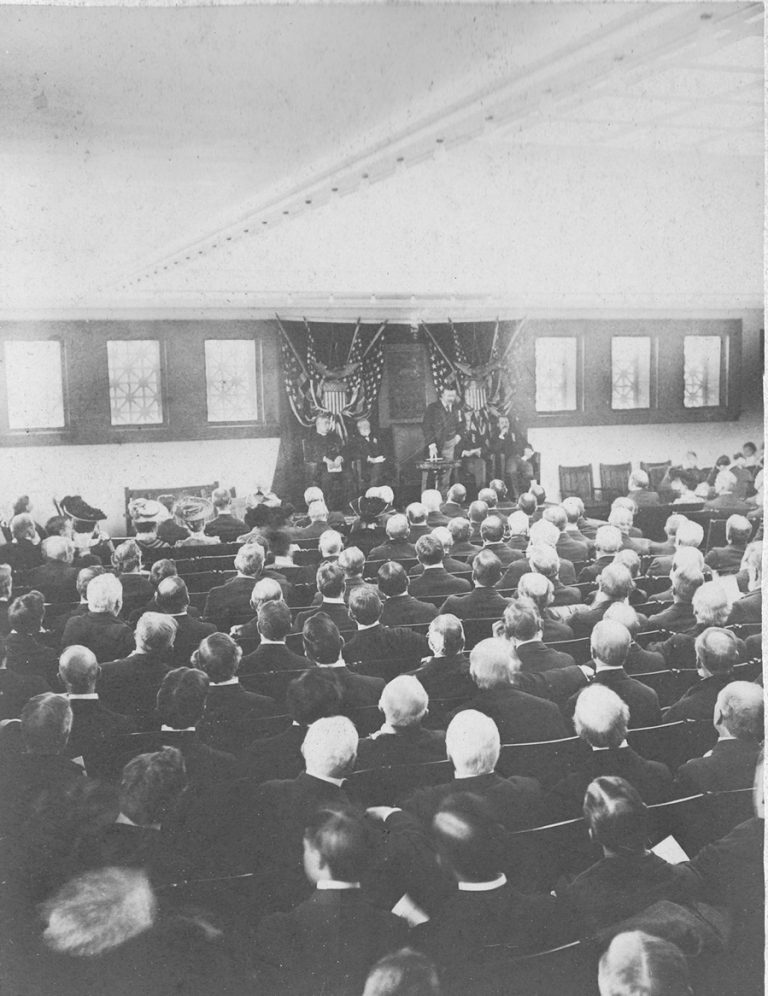

Construction of Carnegie’s new library concluded in 1902. A dedication ceremony followed on January 7, 1903, and the library became known as Central Library. Andrew Carnegie, President Theodore Roosevelt, and other city luminaries attended the event.

Central Library became the main branch for the DC Public Library System. The patrons of the library were never segregated, allowing all communities members to access its resources. However, beginning with the Wilson administration in 1913, the library only hired white staff.

City Beautification and Displacement

The construction of the library was one episode in a series of “beautification” projects. City planners and government officials believed that visual improvements to public spaces would increase the value of property in the city. One mile from Carnegie Library, the destruction of the notorious Swampoodle alley culminated in the construction of Union Station in 1907. Hundreds of alley residents were displaced by this development, most of them immigrants of Irish descent.

For some DC residents, the beautification trend significantly improved daily life. For others, it led to forced removal.

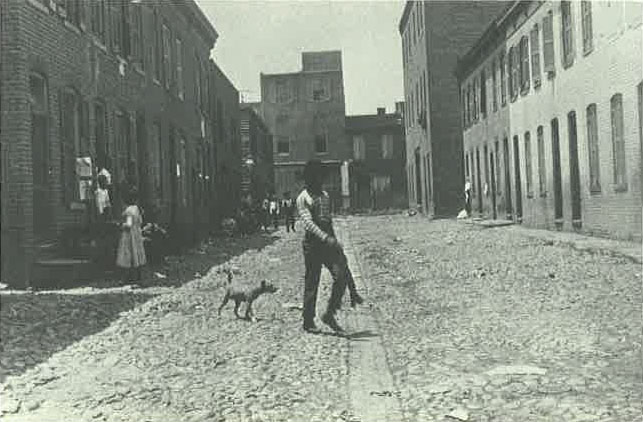

Alley Communities in an Upscale Neighborhood

Even with the upscaling of the area, both black and white residents remained in the neighborhoods bordering Mount Vernon Square. Typically, the houses facing the streets were inhabited by white residents, while the hidden alleyways in the interior of the blocks were inhabited by African Americans. These alley communities developed as a necessity in a city with limited transportation options. Without access to horses, working class people walked everywhere and required homes near their work. This trend wasn’t exclusive to low income populations—even the wealthy travelled by foot in what historians have termed “the walking city.”

Courtesy of the Washingtoniana Collection, DC Public Library.

Segregating Real Estate 1910-1950

How Mount Vernon Became Black and Upper Northwest Became White

The residents living in the Mount Vernon Square were racially mixed at the turn of the twentieth century, as were those in the far upper northwest of the city. A substantial black community known as Reno City existed adjacent to where Tenleytown is today.

As a new streetcar line extended up Wisconsin Avenue, developers and white homeowners advocated for the removal of Reno City from the area. The campaign succeeded as the National Capital Park Commission oversaw the destruction of Reno City from 1928 through 1951. The developers, with the help of the government, transformed the upper northwest of the city into a white residential area. White homeowners moved into newly constructed, all-white communities, and benefited from federally subsidized mortgages.

Because Mt. Vernon’s homes were older and African Americans lived in the area, those homes did not have access to favorable home loans. African Americans bought the once prestigious homes lining the streets of Mount Vernon Square. They bought these homes on the contract system, which resulted in them paying the previous owners directly for the homes with high interest rates and short-term contracts.

Racially Restrictive Covenants

D.C. developers, private citizens, and the courts helped lay the groundwork for real estate practices that promoted racial segregation. In the 1910s, homeowners and developers in Washington, DC began adding racially restrictive covenants to the titles of properties. These covenants, enforced by the courts, prohibited future property sales to African Americans. They were most common in subdivisions with smaller lots, which were more affordable and more likely to attract black home seekers.

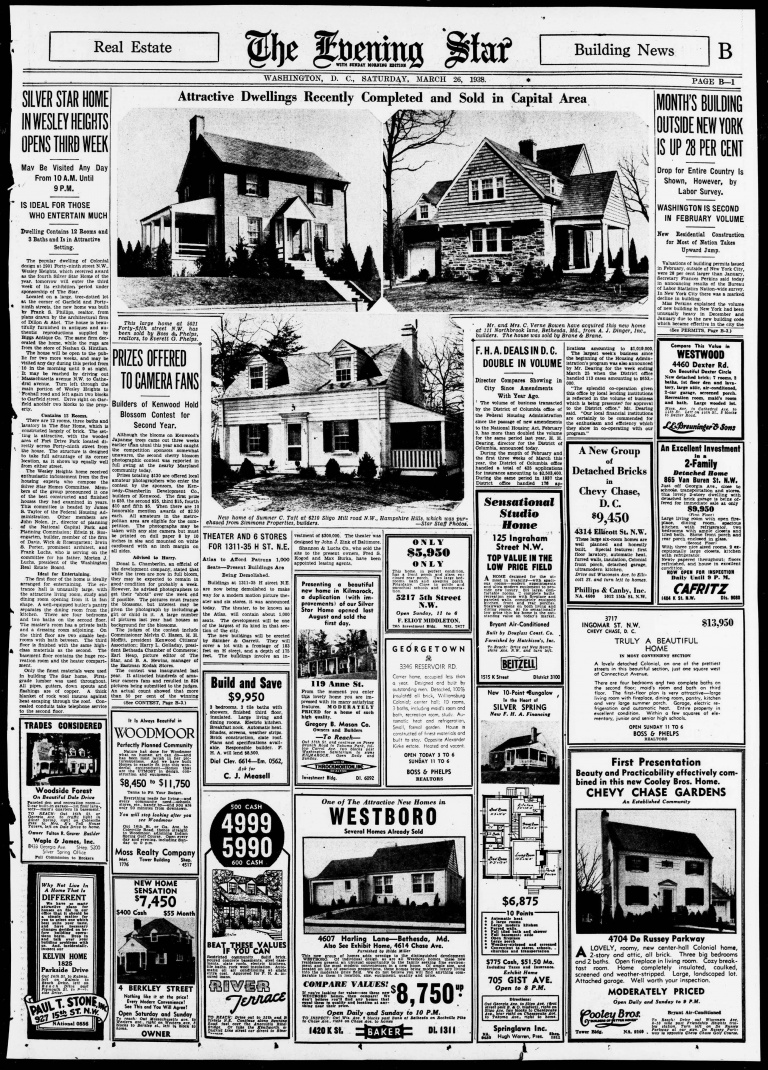

Federal Housing Administration

Congress and President Roosevelt created the Federal Housing Administration in 1934, an agency which institutionalized racially discriminatory lending practices. Prior to the New Deal, homeownership was prohibitively expensive for middle-class families. Bank mortgages typically required 50% down, interest only payments, and repayment in full after five to seven years. The FHA insured bank mortgages that covered 80% of the purchase prices, had terms of twenty years, and allowed borrowers to build equity in their homes while they paid off their loans. The FHA’s appraisal standards included a whites-only requirement; racial segregation became an official requirement of the federal mortgage insurance program. The agency judged racially mixed neighborhoods and all-white neighborhoods that were at risk of future integration as too risky for insurance.

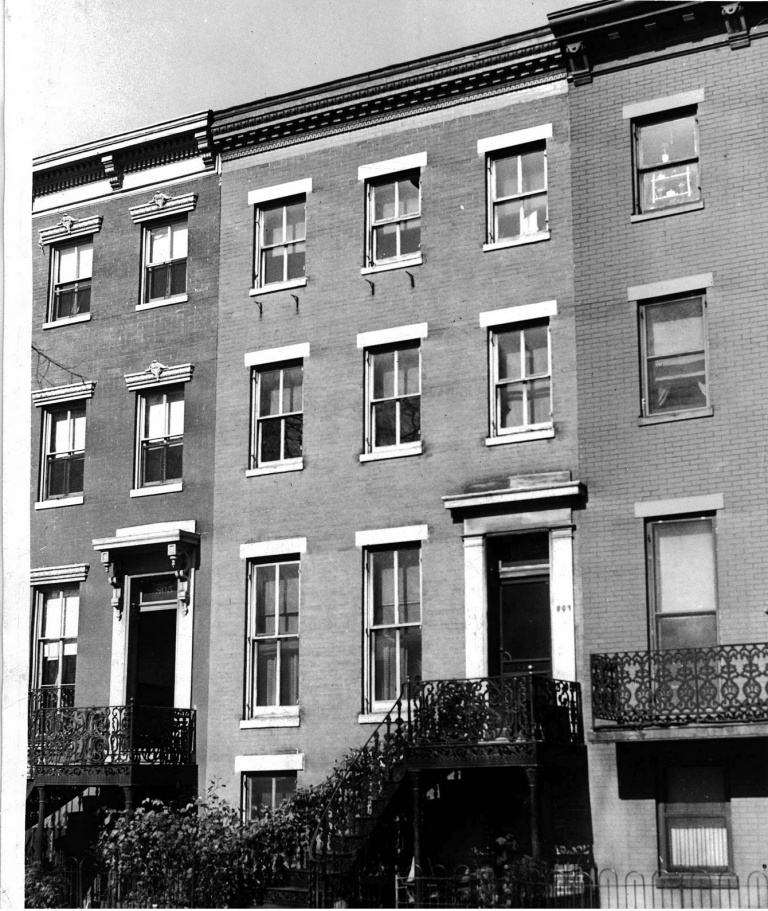

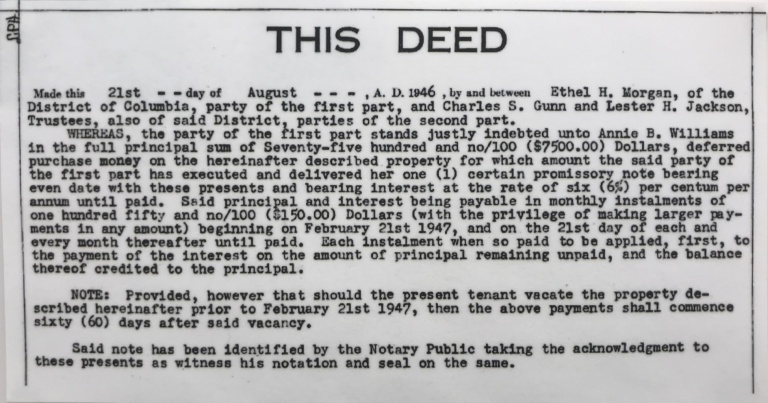

Purchasing on Contract

In 1946, Ethel H. Morgan, a white woman, purchased this home, 803 Mount Vernon Place NW, from Annie B. Williams, a black woman. The townhome had been constructed in the late nineteenth century across the street from the Carnegie Library, where the current Convention Center stands. Even though Morgan was white, because the home was older and African Americans lived in the neighborhood, the purchase was not eligible for an FHA loan. In order to buy the townhouse, Morgan entered into a five year contract with Williams. The contract required her to pay monthly interest payments that did not give her any equity in the house. At the end of the five-year term, she needed to pay $10,000 to Williams or lose the home. After the purchase, Morgan did not move into the home. She rented rooms out in the house and became an absentee landlord. Courtesy of the DC Office of Tax and Revenue Recorder of Deeds.

Urban Renewal in Mt. Vernon 1950-1980

Urban Renewal

Harry Truman established the federally funded “urban renewal” program when he signed the Housing Act of 1949. The act dictated that federal funds would be utilized in urban areas across the country to “redevelop” urban areas deemed as “slums” suffering from blight. The act initiated a movement in cities across the country to “revitalize” or “renew” neighborhoods primarily inhabited by people of color. Washington, DC had one of the country’s earliest urban renewal projects in Southwest DC. The project displaced 23,000 residents from a predominately African American neighborhood. Local critics referred to the project as the “Negro Removal Program.”

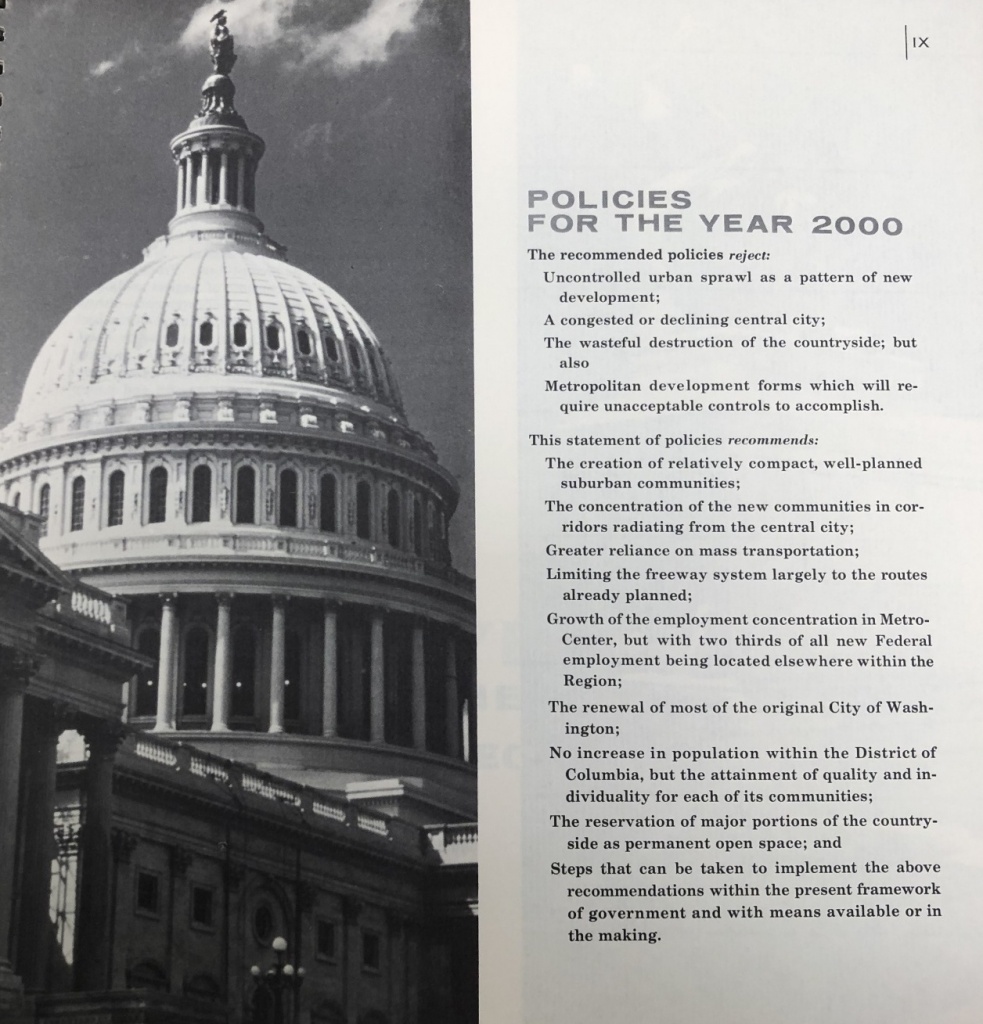

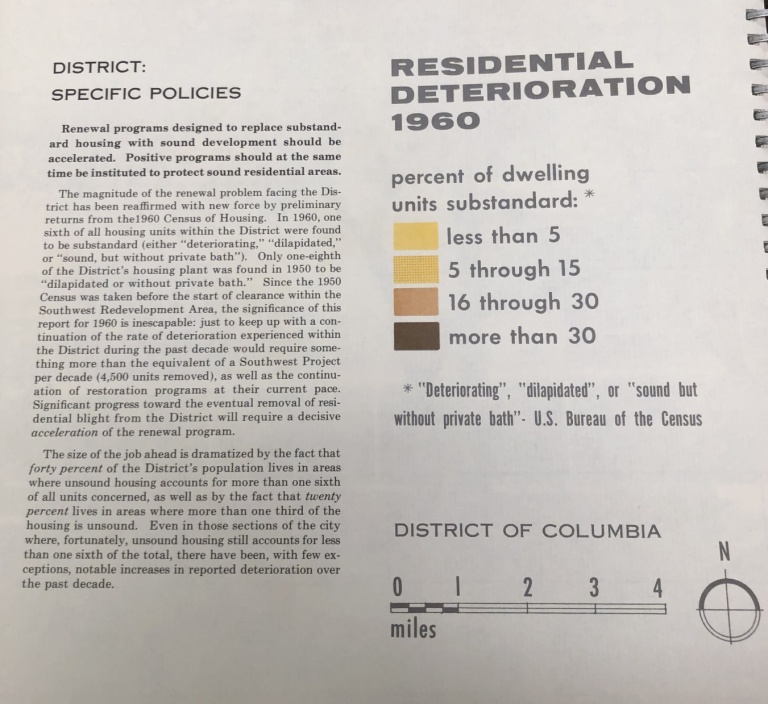

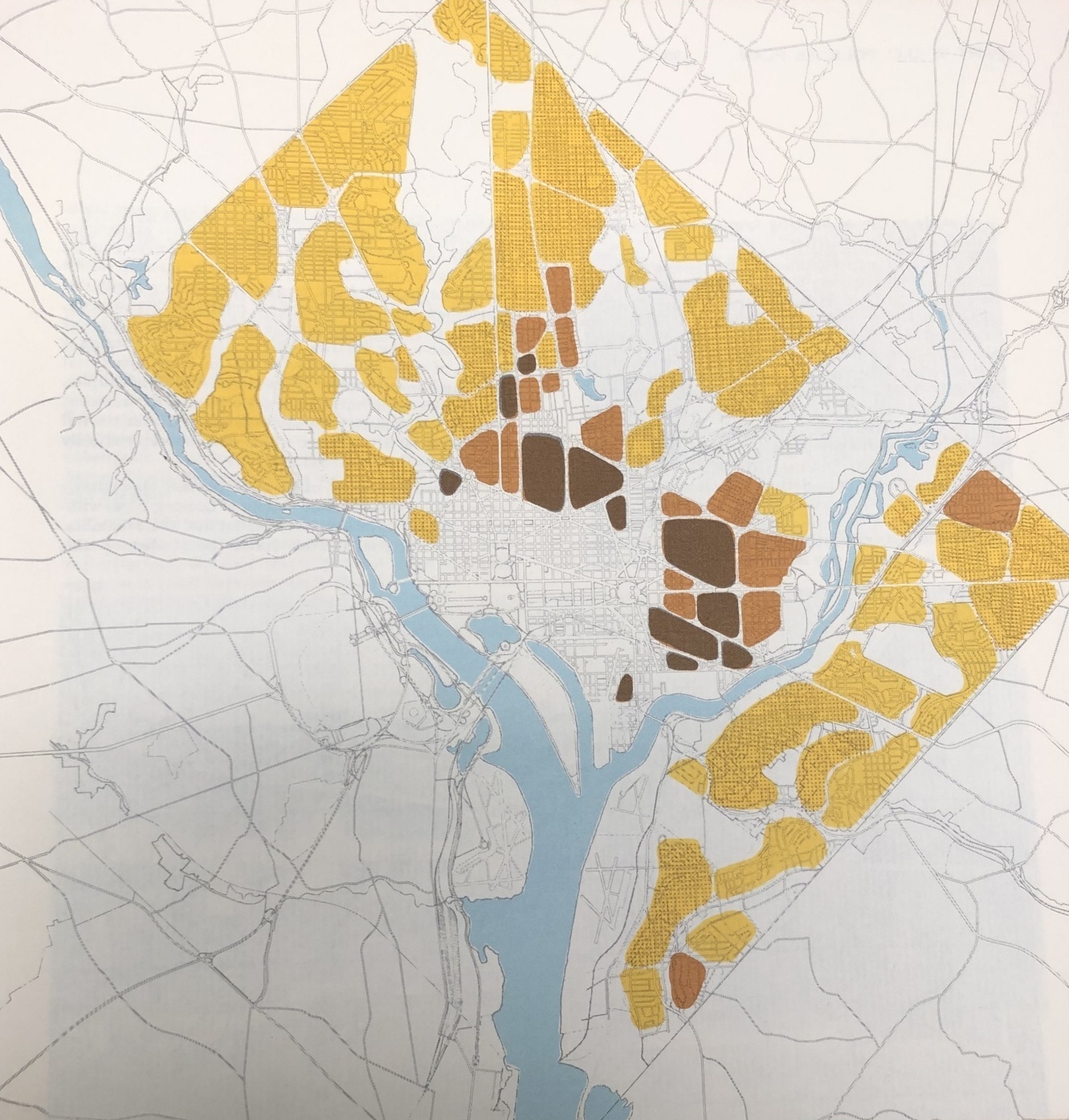

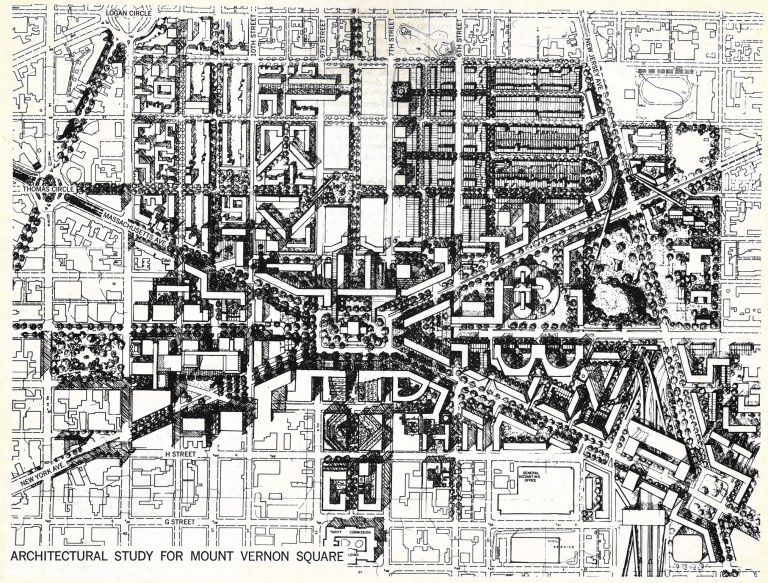

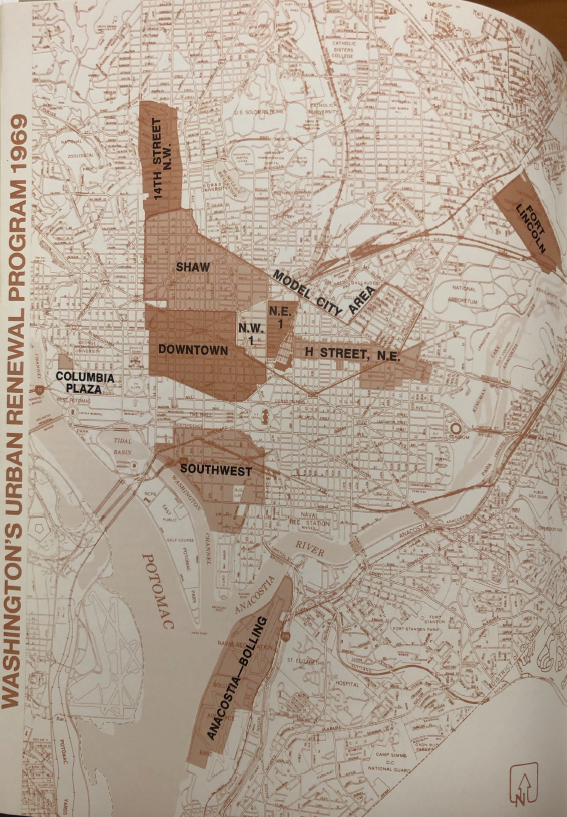

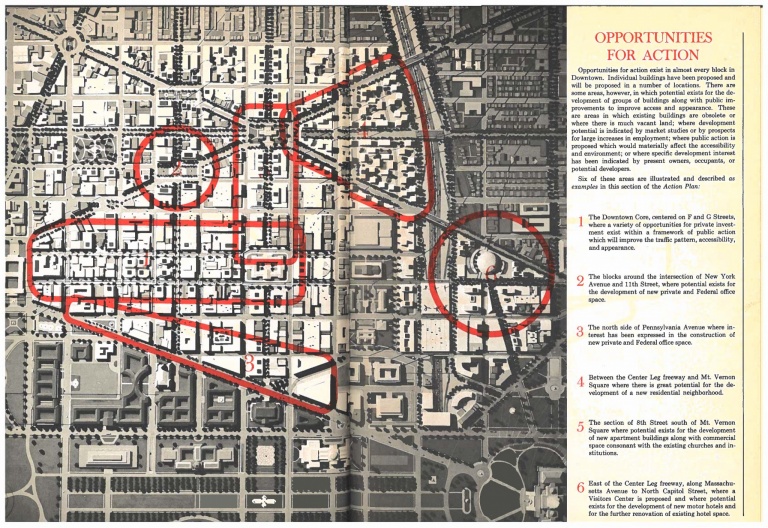

With the Southwest DC project nearing completion, public officials lauded its successes and called for a “decisive acceleration of the renewal program” that focused downtown. Well before the 1968 uprisings, in 1961 officials published “A Policies Plan for the Year 2000” that called for “the renewal of most of the original City of Washington.” The plan identifies areas inhabited by African Americans, especially the areas around Mount Vernon Square, as regions experiencing “residential deterioration” in need of “renewal.” The plan included drawings depicting the area completely transformed— their homes and communities erased and replaced with multi-story apartment buildings and offices. African Americans were targeted by Urban Renewal and locked out of the new housing developments.

This map and key identify areas with “residential deterioration” in DC in 1961. With population growth as the cause of “residential deterioration,” the Plan recommends urban renewal as the answer. Courtesy of Gelman Special Collections, George Washington University.

Following the Urban Rebellion of 1968, the city worked with the federal government to craft the Urban Renewal Plan in 1969. The plan reiterated most of the major points of the 1961 Action Plan, yet it skillfully crafted a narrative that would persist to this day, blaming rioters on the destruction of the neighborhood. In fact nearly all the the neighborhood destruction occurred as a result of the Urban Renewal programs themselves.

Courtesy of DC Public Library Washingtoniana Collection.

Convention Center in Mount Vernon Square

In the early 1970s, the Washington Board of Trade pressed for the construction of a new convention center. Its proposal recommended that it be constructed in the Mount Vernon Square area. The proposal argued, “the fringe of the Central Business Area is one of the most rapidly deteriorating residential areas in Washington. Heavy traffic, noise, smells, and other effects of non-residential uses are only some of the conditions which have made this type of area undesirable as a living-place.” While authors of the report concluded the area to be uninhabitable, the planners were well aware that there were a large number of people of color that lived in the area.

Throughout the process, city officials and construction firms used increased job opportunities for minorities as justification for the center’s construction. However, Mount Vernon area’s low-income minority populations were most negatively impacted by the establishment of a convention center, built between 1980 and 1983.

The city destroyed the old convention center in 2005. Shortly after it had been constructed in the 1980s, the Washington Board of Trade complained it was too small for the city’s convention needs.

Courtesy of Historical Society of Washington.

Displacement and Redevelopment 1980-2005

Chinatown

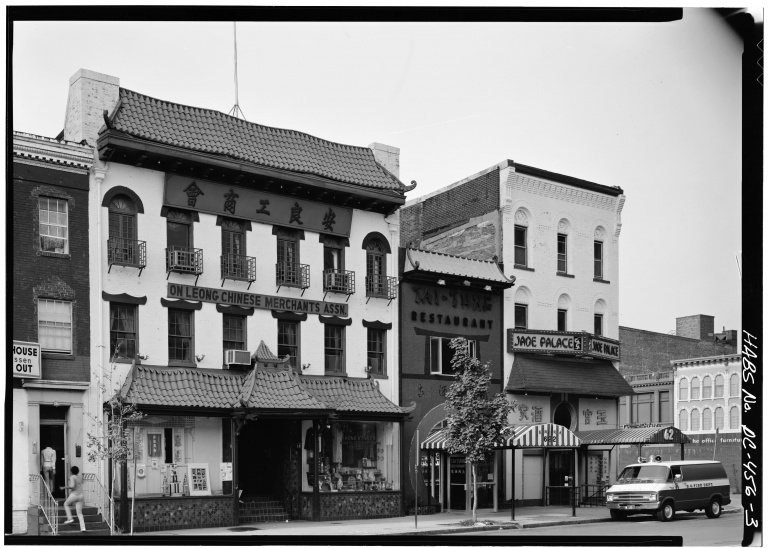

The local D.C. government proposed building the Washington Convention Center in Chinatown during the mid-1970s. Residents of Chinatown presented fierce resistance and managed to alter city plans. The Convention Center was ultimately built west of 9th Street. The large-scale demolitions of the Downtown Urban Revival project and the construction of the MCI Center – now the Capital One Arena, which opened in 1997, ultimately caused widespread displacement in the area.

As developers pitched the plan for the arena, promises of jobs and a better neighborhood were made but ultimately were not delivered for pre-stadium residents. The dislocation caused by rising rent prices for pre-stadium businesses and residents has been disastrous. Barely 10% of the pre-stadium organziations and businesses survived. The remaining residents are largely elderly and housed in teh Wah Luck House, constructed during the District’s attempt to place the old Convention Center in Chinatown. The price of making downtown a destination for professionals and tourists has been that its previous residents must undergo dislocation and marginalization.

During the 1970s, residents of Chinatown sustained many of their cultural celebrations, such as the Chinese New Year parade, while the city aggressively demolished buildings as part of the Downtown Urban Renewal project. The annual parade continues to this day.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Barely 10% of the businesses and organizations in Chinatown before the construction of the arena have survived its impact. The only building that remains in this image is the On Leong Chinese Merchants Assn. building, which now houses the Chinatown Garden Restaurant.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

During the 1970s and 1980s, as part of the Downtown Urban Renewal project, the city demolished most of the buildings where the MCI Center would eventually be located.

Courtesy of DC Public Library Washingtoniana Collection.

While the MCI Center, now Capital One Arena, had a greater impact on displacing businesses and residents from Chinatown, it appropriated Chinese lettering in an almost comical effort to blend in.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

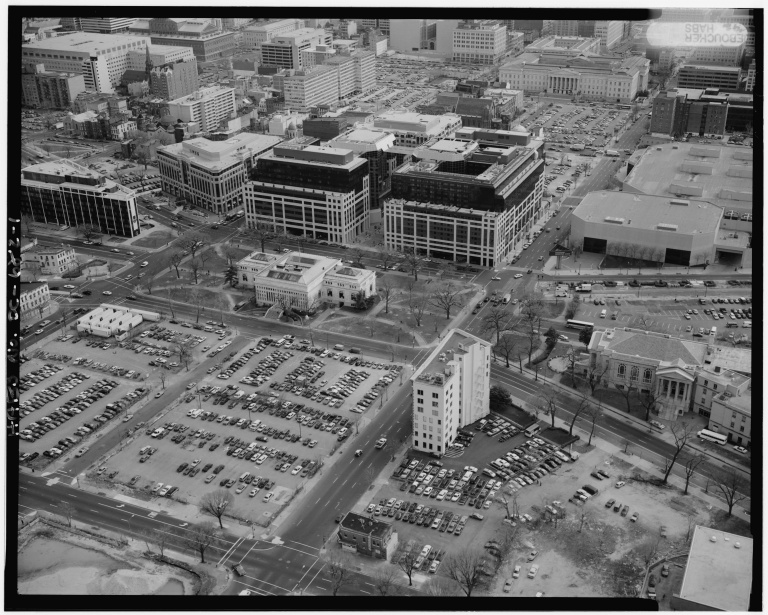

The image is of the shopping district along 7th Street between Mount Vernon Place and L St NW. In the 1970s, renewal efforts led to the demolition of these buildings. The area became a parking lot for a quarter of a century before the current Convention Center was built on this land.

Courtesy of Historical Society of Washington.

Empty Promises at the New Convention Center

After just a couple years, the Washington Board of Trade complained that the original convention center was too small to accommodate the conventions they hoped to attract. After a decade and a half of efforts, in 2002 DC officials approved the construction of a new convention center on the footprint originally designated for Federal City College. Economists associated with the convention center publicized its alleged potential to bring more jobs and money to the area. Independent economists, however, determined that these were empty promises.

At a cost of $16 million dollars, the city demolished the old convention center in 2004 and 2005 and built a parking lot. The land was turned over to private developers who began building CityCenterDC in 2011. When the first phase opened in 2015, it included luxury apartments, offices, and high end retail establishments.

Preservation and Gentrification 1999-2019

Historic Preservation and Gentrification

In 1969, shortly before the DC Public Library moved its central branch from the Carnegie Library, historic preservationists successfully applied to have the building placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Three decades later, in 1999 preservationists succeeded in having Mount Vernon Square listed as a Historic District. During these three decades thousands of people had been displaced as their homes had been demolished.

The application to list Mount Vernon Square as a Historic District lamented the loss of some historic structures, but overall lauded the role the library played in the neighborhood’s transformation:

The erection of new buildings on vacant lots, the multi-million dollar restorations, modest rehabilitations, and landmark designation of historic buildings such as the Yale Steam Laundry, the O Street Market, and the Carnegie Library have made great strides in rejuvenating the 7th Street corridor, Mount Vernon Square, and the greater Mount Vernon neighborhood.

Like the beautification movement of the early 20th Century, preservationists had no interest in sustaining the communities of people that made the area their home.

Today at Apple

The Mount Vernon Square neighborhood has endured waves of urban renewal efforts and subsequent displacement. Rapid transformations continue into the twenty-first century. Property values continue to skyrocket as local government incentives attract large companies to develop DC. A recent study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that DC has had a greater intensity of gentrification and more displacement of African Americans than any other city in the country. These changes have been traumatic for many long-time residents, who continue to feel the emotional consequences of this physical disruption.

In 2018, Apple Inc. announced the renovation of the Carnegie Library, turning its first floor into the east coast flagship. As companies like Amazon follow suit, these patterns are likely to all to persist without major political and social interventions.

A closed Carnegie Library, abandoned by the DC Public Library in 1972, with chain link fence around the property.

Courtesy of Historical Society of Washington.

Carnegie Library Closes

Carnegie Library closed to the public in in 1972. Ultimately the building remained officially closed over the next twenty years as urban planners debated what to do with the building. Some hoped to have it become part of a downtown university, and others argued that it should be part of a new convention center. In 1999 the Historical Society of Washington moved in and have remained there since.

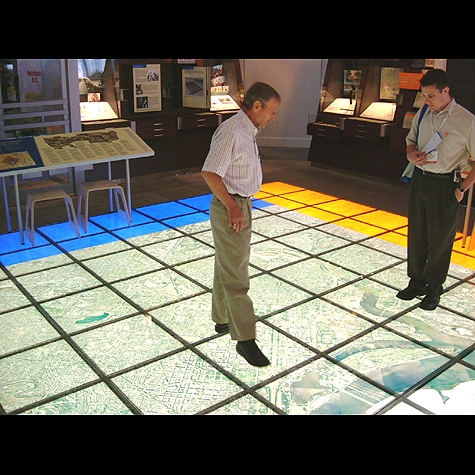

City Museum at Carnegie Library

The Historical Society of Washington created The City Museum in 2003, in the old Carnegie Library. There were two main exhibits: “Washington Perspectives” and “Washington Stories.” City officials hoped that this museum, along with the convention center, would bring tourists and fuel redevelopment. Instead, it attracted few people and closed only a year later.

Planned Destruction: Aerial Imagery of Mount Vernon Square and Its Surroundings, 1949-2017

These images provide an aerial overview of dramatic neighborhood transformations that took place between 1949 and 2017. The early images show a built landscape that includes residential homes, apartment buildings and small businesses in all directions surrounding Mount Vernon Square. Between 1964 and 1981, huge swathes of these neighborhoods have been demolished. The construction of the first convention center intiatates major new construction in Chinatown, which can be seen in the 1988 map and the ones that follow. The concluding map of 2017, as compared with the 1949 map that the video returns to, starkly illustrates how much was lost and how much has changed. Nearly every building south of Massachusetts Ave. and New York Avenue, east of the Union Station railroad tracks, north of F Street, and west of 14th Street has been demolished and rebuilt. These changes did not just occur as result of abstract market forces. A tremendous amount of planning, beginning as early as 1961, has steered this transformation.

This exhibit has been produced and curated by:

Dan Kerr and his Engaged Community History Class at American University: Marita Anastasi, Hannah Byrne, Rachel Hong, Lina Mann, Abigail Seaver, A. Drew Smith, Kai Walther

Special thanks to:

Street Sense Media, including: Bryan Bello, Leila Drici, Levester Joe Green, Robert Warren, Reginald Black, Angie Whitehurst, Morgan Jones

Sheila White, Sasha Williams, Chon Gotti, Carlton Johnson, Jeffery McNeil, Jennifer McLaughlin, Ken Martin , Willie Schatz

Maren Orchard, Humanities Truck

Curtis Harris, American University

Meagan Snow, American University Library

Anne McDonough and Jane Levey, Historical Society of Washington, DC

Leah Richardson and Kierra Verdun, Special Collections Research Center, GWU

Digital Exhibit by: Kimberly Oliver, Humanities Truck

Add your stories and interpretations:

What stories were left out of this exhibit?

What do you want to share about Mount Vernon Square?

What do you think causes neighborhood change?