Since March, the Humanities Truck has suspended all events and in-person gatherings due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a grad student at American University, the initial impact of the pandemic felt like whip-lash. Within the span of a week, I was told that my classes would be online, and that I would be required to work remotely. I struggled to adjust to this new online format, and I felt the impacts of social distancing as I made the decision to stop seeing my friends and the community I’ve built through my first year of graduate school. News articles and videos of the pandemic’s devastating impact on the lives of thousands of people across the globe filled my social media feed. In California, my younger sister had to move out of her college dorm and move back home. My mother lost her job as a result of school closures, and has struggled to apply for unemployment benefits. I share my experiences here because I know they’re not unique — the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted us all.

Building and sustaining relationships with communities is central to the Humanities Truck’s mission, and as a graduate fellow on the project, I’ve participated in discussions in which we are completely rethinking how to engage virtually with our community partners. How can we connect with people when we can not be physically present with them? How can we use the Humanities Truck platform to celebrate the resilience of our communities and draw attention to the impact of COVID-19?

#MobilizingMemories

The Humanities Truck is embarking on a new virtual oral history project called From Me To You, to document people’s experiences during COVID-19. With this project, we want to highlight resilience and personal networks by asking: How has COVID-19 impacted you? Who or what has kept you going in this moment of crisis? What do you hope we will learn from this?

Traditional oral histories are conducted by people who have received formal training in oral history methodology. However, because of social distancing practices during the pandemic, the Humanities Truck is collecting crowdsourced oral histories, which are oral histories conducted by the individual traditionally considered the interviewee. We provide potential interviewees with a basic set of questions and recording techniques to allow them to record and submit their own oral history videos.

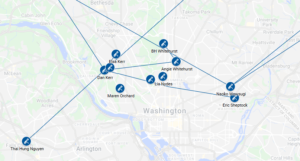

If you are interested in submitting a video and becoming a part of our community map, please visit our submissions page or reach out to us via email or on social media with your questions!

What happens after I submit a video?

Once you have completed and submitted your video, we ask that you reach out to others in your personal network and invite them to participate — this is part of what makes our project unique! Our aim with this project is to visualize these networks and the relationships that sustain us. Your collective stories will be added to our community map where we draw threads between the videos, allowing participants to see how our stories and experiences relate and connect to others.

Currently, the project has collected 22 oral histories — 14 of these from the DMV and 8 from across the United States. Each of the oral histories networked on our map has a story to tell, as our participants share their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In her oral history, Angie Whitehurst shares cartoons she’s created for Street Sense in response to COVID-19 that include important messages about creating community-led change and staying home to keep each other safe. In her video, she says “Stay in, and we better stay in and be safe until we work this all out. Don’t worry about going stir crazy. Find something to do like I did. Draw cartoons. Share them.” Angie’s cartoons explore urgent social issues that have been recently exacerbated, including the racial dimensions of health, criminalization, and incarceration during the pandemic. She ends with a call to help our communities, saying “Now is the time for all good people to come to the aid of each other. Human kindness is what we really need right now. We must help our neighbors.”

Britt Dorfman addresses her concerns surrounding her high-risk health status during COVID-19. Britt has a chronic disease called Crohn’s disease, and although it is in remission, she still takes immunosuppressant medications. She shares her concerns, saying that, “It gives me a lot more anxiety as someone who’s in the high risk category, if I were to get COVID-19 it’s possible that I would have more serious illness.” Britt has managed her anxieties by staying connected to friends and family, spending time with her cat, and attending virtual Shabbat services. She finishes her video by saying, “And if there’s one thing I hope that we can learn during this time, it’s that everyone is valuable and no one is disposable. Everyone plays a really important role in this world no matter what.”

The importance of community during COVID-19

At the Humanities Truck, we believe in the resilience of communities. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted our everyday lives on a global scale, and we experience it on a local level. Many of us have witnessed first hand how ineffectual our government’s response to the pandemic has been, as we struggle with physical distancing and loneliness, unemployment, affording necessities and groceries, making rent payments, accessing healthcare, and more.

In response to this, communities have coalesced, sometimes building on existing frameworks, but also where they might have not existed before. Social groups, students, apartment buildings, and neighborhoods have come together in cooperation and solidarity to create “mutual aid” networks.

According to Big Door Brigade, and Dean Spade and Ciro Carrillo in their video:

Mutual aid projects are a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government, but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable.

Rather than relying on the government, communities are self-organizing by sharing resources, skills, and time to provide for local needs. Many mutual aid networks take the form of Google Docs or Sheets with links to resources that can be added to and shared. Others are going one step further and sending out surveys and polls to organize healthy volunteers to help with tasks like delivering groceries and medication. Above all, mutual aid values dignity, transparency, and long-term commitment.

The current Humanities Truck initiative “From Me to You,” seeks to document and collect our experiences during the pandemic — however, we also recognize the importance of access to resources and information to address our economic and physical well-being. For this reason, I’ve compiled a list of mutual aid documents with links to resources and information relevant to the DMV, such as: D.C. Covid Connect: COVID-19 Washington, D.C. Community Resources + Up-to-Date Health Information, DC Resources Covid-19, and DC Mutual Aid Spreadsheet. Visit the Humanities Truck website to view the full list of resources.

Bibliography:

Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. “Collective Care Is Our Best Weapon against COVID-19.” Accessed May 26, 2020. https://mutualaiddisasterrelief.org/collective-care/.

“Covid-19 Oral History Project.” Accessed May 26, 2020. https://sites.google.com/iu.edu/covid-19oralhistoryproject/about.

McMenamin, Lexi. “What Is Mutual Aid, and How Can It Help With Coronavirus?” Vice (blog), March 20, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/y3mkjv/what-is-mutual-aid-and-how-can-it-help-with-coronavirus.

“What Is Mutual Aid? – Big Door Brigade.” Accessed May 26, 2020. https://bigdoorbrigade.com/what-is-mutual-aid/.