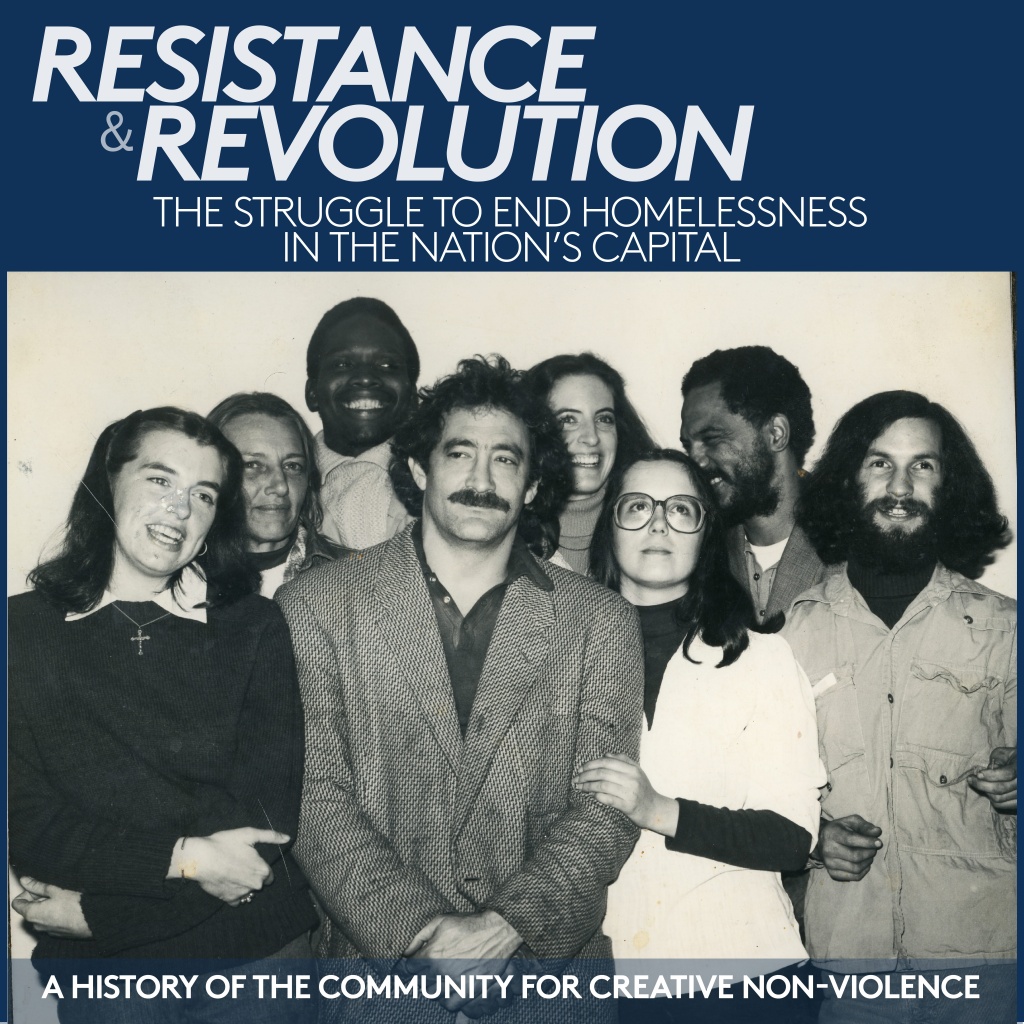

A small group of activists’ efforts revolutionized our nation’s policies to address homelessness and created lasting change on the streets of DC.

In 1970, a Catholic Priest and graduate students at the George Washington University, formed a group to protest the Vietnam War: The Community for Creative Nonviolence (CCNV). CCNV quickly turned their attention and efforts to addressing the structural violence of poverty on the streets of Washington, DC.

Over the next two decades, led by Mary Ellen Hombs, Mitch Snyder, Carol Fennelly, and Harold Moss, as well as many others, CCNV gained a national reputation for its controversial and theatrical protest methods. With a feverish passion for change, the group embraced a radical Christian pacifist world view that was influenced by Gandhian approaches to non-violence.

1970-1975: CCNV Origins

Soldier of the Streets - Mitch Snyder

Known as a “soldier of the streets,” Mitch Snyder’s background influenced his abrupt, impatient, impolite commitment to non-violence. Born in 1943, Mitch Snyder grew up in a lower middle-class neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York in a Jewish household. His parents divorced when he was nine, and when his father left, Snyder became responsible for supporting the family. As a teenager, he remembered, “I didn’t respond very well to authority, and began getting into trouble.” He was arrested fifteen times by the age of sixteen for petty theft, breaking into parking meters, and “nasty things like that.” As a result, he was sent to reform school in upstate New York.

At 20, Snyder married, had two children and began to settle down as he worked his way up from a mailroom clerk, to salesman, to management consultant on Wall Street. With the nationwide anguish over the Vietnam war in 1969, Snyder, now 26, “snapped” and left his job and family and to take to the road. In 1970, he was arrested in Las Vegas while driving a car that had been rented with a stolen credit card. He was convicted and given three years, of which he served two in federal prison in California and then in Danbury, Connecticut.

The First Fast

While in prison, Snyder befriended Daniel and Philip Berrigan, two anti-war priests who had been imprisoned for destroying draft records. With other anti-war prisoners they formed a group that would become known as the Danbury 11. The group introduced Snyder to Christian anarchism and religious non-violence as they protested against the prison’s institutionalized injustices and the Vietnam War. During these protests, Snyder went on his first hunger strike, the strategy he successfully embraced in the 1980s to establish the CCNV Shelter. From prison, he wrote, “resistance must be a lifestyle, not simply a tactic.” On his release in 1973, a former inmate and friend, Tom Ireland, asked him to come to Washington, DC and join the Community for Creative Non-Violence.

Foundation of CCNV

Edward Guinan, an international financier turned Catholic priest founded CCNV in 1970 to “resist the violent, to gather the gentle, to help free compassion and mercy and truth from the stockades of our empire” (Signal Through the Flames, 56). He was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, the civil rights movement, and the violence of the Vietnam War.

Image courtesy of Larry Morris and The Washington Post

Beginning to Focus on the Homeless

In its early years, CCNV focused on protests against the Vietnam War. However, after a night in jail, Guinan began to grasp how poverty, like war, breeds violence. In their continued effort against structural violence, Guinan and CCNV announced the opening of a soup kitchen, Zacchaeus Community Kitchen. Named for the biblical figure Zacchaeus, the opening solidified CCNV’s path forward working on issues of poverty in the District.

Euclid House: From Global to Local Protest

Not everyone in CCNV was pleased with the group’s shift in focus to poverty and service. Several members, including Mitch Snyder and Mary Ellen Hombs, remained committed to focusing on “worldwide oppression and violence.” To address the difference, CCNV agreed to established Euclid House in 1974 pictured here with Mary Ellen Hombs (left) and Carol Fennelly (right) on the steps outside. The others, including Ed Guinan, lived in the N Street House. Early on, the Euclid House community focused on famine in the Sahel, apartheid in South Africa, military intervention in Central America.

It was not until the group began reading and reflecting upon Mahatma Gandhi’s writings that they began to recognize the importance of working locally and returned to Ed Guinan’s approach. While they returned to a local focus, the group never abandoned its commitment to address injustices around the world. CCNV activists developed a unique capacity to shift the scales in their focus from the personal, to the local, to the national, and to the global.

No To Clemency, No To Your War

While the N Street community began to focus more on issues of poverty, the Euclid House group remained committed to anti-war activism. In March 1975 CCNV members from Euclid House staged a sit-in inside White House to protest President Gerald Ford’s decision to offer clemency to Vietnam War draft resisters. From CCNV’s perspective, resisters committed no crime, and were undeserving of criminal charges, making offers of clemency an absurdity designed to cover up the immorality of the war. Mitch Snyder and Mary Ellen Hombs both were arrested. It was Snyder’s first arrest for political activity. By the end of April, the Vietnam War was over and the members of Euclid House shifted their attention to other global issues.

1975-1980: The Early Fight for Shelter

The Fight For Fairmont Shelter

The Euclid House Community was situated, unknowingly, in a neighborhood that was severely impacted by governmental urban renewal policies. The 14th Street Urban Renewal Project, which began in the 1960s, resulted in a large number of the homes in the neighborhood being abandoned, boarded up, burned down, and demolished. By 1976, the substantial loss of housing left many in the community without homes. As their neighbors increasingly came to them seeking assistance, the Euclid Community first realized the importance of establishing a shelter.

To address the crisis, in 1976, CCNV occupied a 38-room house at 1361 Fairmont St NW, in the heart of the Columbia Heights neighborhood, which had stood vacant for seven years. They demanded the DC government use the house as an emergency homeless shelter. The city granted the group permission to renovate the building, and CCNV spent several years and thousands of dollars repairing it. During this campaign Harold Moss and Carol Fennelly joined CCNV. CCNV struggled to secure funding for their work and remained frustrated by the lack of support from area churches. In 1978, officials took back control of the Fairmont house and tore it down, reportedly for safety reasons, setting the stage for the struggle to secure a shelter downtown.

The photo shows the abandoned, front side of the Fairmont Building (below). Turning the building into a shelter would have given it a new purpose.

A CCNV sign in front of the Fairmont Building declaring their intent to create the future shelter.

Photo courtesy of Nancy Shia, private collection

CCNV hoped to rebuild Fairmont Building. The newspaper clipping documents the struggle they faced finding funding. As the repairs languished, Mayor Harold Washington’s administration put an end to the project and demolished the building in September 1978.

The Fight For Housing

This poster, designed during the Fairmount campaign, highlighted the Euclid House Community’s new understanding of the violence in their own neighborhood. Their awareness of the suffering experienced by their neighbors who had lost their homes prompted them to take on the Fairmount campaign.

Through her research, Mary Ellen Hombs had discovered that city property values were rapidly increasing, and over 2,300 families had been evicted in 1976. Over 99% of the area’s rental units in the city were full while the city owned 4,000 pieces of property, most of which were abandoned buildings. These properties were being saved for future redevelopment. Real Estate speculation was driving people from their homes and neighborhoods.

Protesting Holy Trinity Catholic Church

As they shifted their focus towards housing and issues of poverty, CCNV campaigned for local churches, including famed Holy Trinity Parish in Georgetown, to donate funds and open their doors to the impoverished. Father James English, the priest at Holy Trinity, told CCNV that their budget was dedicated to building renovations. In response, CCNV enacted a series of protests including distributing leaflets, staging church stand-ins, and one of Mitch Snyder’s life-threatening hunger strikes. The 10-day hunger strike nearly killed Snyder and stirred up controversy and debate. This event in 1978, affected the organizational dynamics, creating a permanent breech within CCNV as the N Street Community strongly objected to their tactics. Ed Guinan distanced himself from Snyder, and later reflected, “The lesson of Trinity was not to attack your base while you’re trying to build it.”

Shown here is Father English’s April 1978 response to CCNV in which he declines to give money to shelters, explaining the renovations and spending. The letter arrived the same time the city issued a notice terminating CCNV’s tenancy of Fairmount. English’s response incited the protests for the remainder of the year.

CCNV members passed out these leaflets to parishioners at Holy Trinity during the weekend masses. The literature highlighted the hypocrisy of the church’s spending priorities. The protestors were often met with hostility from parishioners who saw the protestors as self-righteous, arrogant, and judgmental. One parishioner slapped a pile of these leaflets out of Mary Ellen Hombs’ hands while she shouted expletives at her.

Appealing to the President

As the Euclid House branch of CCNV became increasingly isolated in Washington’s activist circles in the wake of the Holy Trinity and Fairmount fiascos, Mitch Snyder sent a letter to President Jimmy Carter informing him of the group’s plans to shelter the unhoused that winter. The group’s flexibility in shifting their focus from the local to the national levels explains, in part, how they went from being a vilified and widely disliked group of radicals to become the country’s most influential activist organization in the fight against homelessness.

Marion Barry and CCNV

CCNV had high hopes for Marion Barry as he ran for Mayor against the incumbent Mayor Harold Washington. Washington’s administration had been responsible for the demolition of Fairmount House, and Barry, who had a reputation as an activist for the poor, promised to fire Washington’s Housing Director as his first act. Upon assuming office, Barry declared in a public address, “SHELTER IS A BASIC HUMAN RIGHT,” and promised to open a shelter in every quarter of the city. He turned over the operation of the city run Pierce School and Blair School shelters to CCNV.

Barry, however, backed away from his commitment to shelter as a basic human right. As every shelter that opened was quickly filled to capacity, in 1980 Barry’s administration threatened to close shelters, cut back funding of others, and began conducting police raids of drop-in centers and shelters. To counter these policies, as this 1980 flyer and letter demonstrates, CCNV targeted Barry in their protests.

This antagonistic relationship would ease somewhat as Barry cooperated with CCNV as they fought the Reagan administration over the Federal City Shelter. But Barry continued through the 1980s to fight against CCNV’s efforts to recognize Shelter as a Basic Human Right.

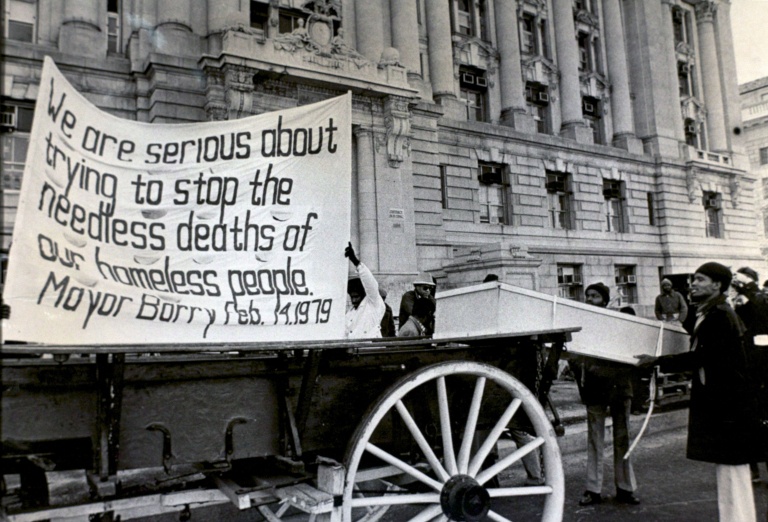

John Doe Funeral Procession

The number of people dying on the streets in the nation’s capital in the late 1970s and early 1980s deeply impacted the members of CCNV. CCNV members were drawn to the writer Leon Bloy’s quote, “We have places in our hearts that do not yet exist. Suffering enters them in order that they might have existence.” In January 1980 an older unknown man died in an abandoned car. In order to give the man a dignified funeral and to highlight the number of people dying on the streets, CCNV fought successfully to gain custody of the body. A horse-drawn carriage with “John Doe’s” coffin led the funeral procession through the city’s streets. CCNV members highlighted Marion Barry’s hypocrisy with the banner pictured above.

1981-1985: Radical Protests

Corpus Christi Fast

The CCNV community saw hunger, homelessness, and the country’s militarism as interconnected. Member Justin Brown explained, “I think hunger, homelessness, war and nuclear weapons are all symptoms of deeper kinds of violence in our lives.” These interconnections came to the fore when the Department of Defense in April 1981 named a new nuclear attack submarine “Corpus Christi” (The Body of Christ).

After a letter-writing campaign and appeals from religious leaders failed to convince the Navy to change the name, Mitch Snyder (in the bed), Carol Fennelly (at his side), and Mary Ellen Hombs (at the foot of the bed) engaged in a Gandhian inspired fast. Fennelly emphasized, “I was fasting on liquids and spiritually, I began to understand my own complicity. The fast was very much a fast of repentance.” Fennelly and Hombs would fast for 42 days on liquids. Mitch Snyder fasted for 54 days and began showing signs that he was approaching the final stages of starvation. He ended his fast after the Navy relented and renamed the submarine, “The City of Corpus Christi.”

The campaign strengthened CCNV’s national network as supporters gathered petitions with 150,000 names and special religious services were held in over 200 cities across the country. This network would prove pivotal in CCNV’s efforts to establish the Federal City Shelter and organize the Housing Now! march.

Welcome to Reaganville

While CCNV maintained their local campaigns throughout the 1980s, they increasingly recognized that the federal government needed to be held accountable for the homeless crisis. President Reagan initially refused to accept that the federal government had any responsibility for the issues raised by CCNV. In response, alluding to the Great Depression “Hoovervilles,” CCNV established “Reaganville” in Lafayette Park, across from the White House on Thanksgiving Day 1981. Seeking to justify inaction, Reagan argued, “people who are sleeping on the grates…the homeless…are homeless, you might say, by choice.” CCNV successfully fought for the right to keep “Reaganville” open across from the White House throughout his administration. CCNV had gone national.

Photo courtesy of www.theccnv.org

Thanksgiving Feast in Lafayette Park, 1981

No one intended for Reaganville to last as long as it did. It emerged out of another plan to bring attention to homelessness, the hosting of a Thanksgiving feast in Lafayette Park across from the White House. While Reagan took his family back home to California to celebrate, on Thanksgiving Day, 1981, CCNV brought huge quantities of turkey, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and pie to the park. Over 600 people gathered to eat. The sheer numbers of homeless people astounded the journalists covering the story. While people ate, CCNV members pitched tents and deemed the encampment Reaganville. The park police stood down, not wanting to arrest large numbers of people on Thanksgiving.

Blood on the White House - Harold Moss

Harold Moss, the only black staff member of CCNV, played a pivotal role in running the shelters and deeply felt the suffering of the unhoused. Prior to joining CCNV during the Fairmount Campaign, Moss, raised in a working-class Catholic family in Memphis, Tennessee, had been a ranked tennis player and a successful chemist at the National Institutes of Health. Along with Mitch Snyder, he spent the winter of 1980-81 living on the streets in order to gain a greater understanding of the suffering of the unhoused. As the Reagan Administration introduced steep cuts to housing assistance and food stamps, Moss argued, “Reagan’s cuts will cause devastation throughout the black community that will take us generations to overcome.” In protest to the federal government’s willful neglect and inaction regarding homelessness, Harold Moss spilled his own blood on the White House gates (pictured below). Moss received a six month prison sentence for this action.

Food Waste and the Giant Campaign

By 1982, CCNV had spent nearly a decade feeding hungry people. The group eventually discovered enormous quantities of edible food in supermarket dumpsters in DC. When they sought to rescue this food, they were chased off by armed guards and threatened with arrest. The group engaged in a campaign to raise awareness, inspired once again by Gandhi, to amplify the issue that enough food to feed 50 million people per week was being wasted by supermarkets every day, including the local grocery chain Giant. At their invitation, Congressman Pete Stark (D-OH) agreed to go on a tour of local dumpsters. This photo of him generated a media frenzy. CCNV followed the tour up by organizing a Congressional luncheon made solely with food gathered from dumpsters. In the wake of this publicity, the Giant Corporation, which had originally rejected cooperating with CCNV, agreed to direct its excess food to local food banks.

Sixty Minutes and the Hunger in the Land of Plenty Campaign

In 1983, CCNV expanded its food waste campaign to focus on the huge quantities of government surplus food that were being stored while Reagan made steep cuts to the food stamp and school lunch programs and people went hungry. By 1983 the US government warehouses were stuffed with 851 million pounds of cheese alone, most of this surplus stored in caves outside of Kansas City. Twenty CCNV members traveled to Kansas City and began a fast on July 4th as they stayed in tents at Liberty Memorial Park.

As the initial press interest waned, those fasting endured intense heat and exposure to the sun. After 28 days on water alone, one faster, Eddie Bloomer, had fallen very ill and began experiencing kidney failure. A sympathetic New York Times article and interest from Sixty Minutes helped galvanize public opinion in CCNV’s favor. The group ended the fast after Secretary of Agriculture John Block would release significantly greater quantities of surplus food and President Ronald Reagan formed the Task Force on Food Assistance.

Sixty Minutes would play a pivotal role in CCNV’s struggle to get federal funds to renovate the Federal City Shelter. The Sunday evening before the November election, Sixty Minutes aired this profile of Mitch Snyder. The next morning, President Reagan signed his executive order committing federal funding to remodel the building.

1986-1989: A Rise to Prominence

Initiative 17

During the heart of CCNV’s struggle against the Reagan administration in 1984, the group demonstrated its growing influence by waging a simultaneous campaign to establish the right to shelter in Washington, DC. More than 200 volunteers gathered 40,000 signatures to put the initiative on the November ballot. Mayor Marion Barry campaigned vigorously against the initiative, arguing it would cost too much money and make DC a haven for the homeless. In November 1984, DC voters sided with CCNV and overwhelmingly supported the measure, establishing Washington, DC as the only city in the country to guarantee access to shelter.

Struggle for Federal City Shelter

Throughout the 1980s CCNV pressured the federal government to address the national and local homeless crisis. During Reagan’s 1983 State of the Union address, the group organized a sit-in at the Capitol Rotunda, resulting in 163 arrests. Hoping to quell the activism, the Reagan administration agreed to turn over the vacant Federal City College building to CCNV in January 1984. As winter ended, the federal government threatened to evict the group to make way for the sale of the building but relented after CCNV staged a large march on the White House.

In possession of the building, eleven CCNV members went on a fast to demand federal funds to renovate it. Snyder fasted for 51 days and ended his protest the day before the 1984 Presidential election when the federal government promised to renovate the shelter. The Reagan administration, however, backed out of its promise and contracted with the DC Coalition for the Homeless to relocate the shelter to Anacostia. CCNV activists began a new hunger strike to preserve access to the centrally located 2nd St. building. The Reagan administration capitulated, funded a five million dollars renovation, and turned the building over to the city of Washington, DC on July 7, 1986. CCNV residents have continued to run the shelter to this day, which has housed as many as 1,700 people per night.

“A Model Shelter”

These images capture the before and after remodel of the Federal City Shelter in 1984 and 1988. With the remodel, CCNV establish a unique “Model Shelter” staffed entirely by volunteer residents. The shelter had an open-door policy, providing a safe haven for thousands of men and women, many of whom were outcasts from other shelters.

Some in the CCNV Community disagreed with the goal of establishing such a large shelter and advocated for smaller, dispersed facilities. Snyder, who had seen how difficult it was to open any shelter in the city, argued, “A centralized shelter is the only way to provide all the services this many people need.”

George Washington University Special Collections, Carol Fennelly Papers, Box 12, Folder 16

Pray-In at the White House

To draw attention to the 40th day of the fast demanding federal funds to rehabilitate the Federal City Shelter, CCNV organized a Pray-In at the White House weeks before the Presidential election. On a cold rainy day, the protestors walked onto the White House lawn while reciting the Lord’s Prayer and were violently arrested by the Secret Service. Pictured here, Mitch Snyder is being escorted to jail. The arrest took a significant toll on Snyder’s health, as he remained bed ridden for the remainder of his fast.

Division and Unity - The Federal City Shelter Fast

Already stretched thin running shelters, drop-in centers, and health clinics along with dumpster diving for food and campaigning for Initiative 17, most of CCNV’s community members opposed taking on the fast to demand the renovation of the Federal City Shelter. Snyder threatened to quit CCNV if the group did not fight on behalf of the 1,000 people living in the shelter. Many in the group were angry at him, but they relented and agreed to support his plan. Only after the fasting became more serious, did the group begin to come together. One member, Wendy Bobbitt recalls that the fasting made her feel close to Snyder for the first time, “I went one year without speaking to him. But you slow down a whole lot on a fast… You feel more love when you’re fasting.”

As Snyder became sicker following the Pray-In, he spent his final days of the fast at Howard University Hospital (pictured here). Supporters from CCNV’s Reaganville, Corpus Christi, Food Waste, and Congressional Luncheon campaigns rallied on his behalf. On November 5, 1984, the day before his second election, President Reagan signed an executive order committing five million dollars to renovate the Federal City Shelter.

George Washington University Special Collections, Carol Fennelly Papers, Box 12, Folders 12 and 18

CCNV - The Movement

This 1988 photo taken on the stairs of the Federal City Shelter documents many of the members of the CCNV community who participated in the struggle to establish the shelter. From its founding through the present, thousands of people have committed themselves to CCNV’s efforts to incite change and eradicate homelessness. Many of their sacrifices have gone unrecognized.

Hate Mail

CCNV’s activism inspired many, but also generated a backlash from others. During the effort to secure funding to renovate Federal City Shelter, President Reagan reversed his promise to provide funding. The federal government then proposed moving CCNV to Anacostia – a move CCNV staunchly opposed. Many neighborhood residents also expressed their concern and opposition to the move. This letter, pictured below, is one example of the hate mail CCNV received. The letter writer failed to realize that CCNV was also against moving to Anacostia.

“We had to capture the attention of people because we were dealing with complete ignorance and absolute invisibility. So, you do that in a very dramatic, high visibility way and in a way that guarantees that people will respond viscerally, emotionally, because it’s only when emotions are aroused that people begin to think.”

Mitch Snyder

This “ALL GOD’S CHILDREN GOTTA SLEEP” flyer was distributed by CCNV to announce an upcoming march to keep the Federal City Shelter open.

George Washington University Special Collections, Carol Fennelly Papers, Box 4, Folder 9

Police look on as protesters gather outside the White House.

George Washington University Special Collections, Carol Fennelly Papers, Box 4, Folder 9

Samaritan: The Mitch Snyder Story

As Mitch Snyder’s acts of civil disobedience gained public attention, local and national media outlets covered his actions and the efforts of CCNV. A made for tv movie starring Martin Sheen as Mitch Snyder, Samaritan: The Mitch Snyder Story, dramatized his life. The jacket on the left belonged to Mitch Snyder himself, and the jacket on the right was worn by actor Martin Sheen on set and in the movie.

Jackets from George Washington University Special Collections, Carol Fennelly Papers, Box 6

Celebrity Attention

Mitch Snyder’s fast in 1984 attracted the attention of celebrities including Cher. As celebrities publicly embraced the work of CCNV, the issue of homelessness entered the mainstream discussion. Snyder and CNNV’s ability to foster relationships with celebrities proved to be an effective method to generate and maintain public attention for their advocacy. The celebrities would play a critical role in building support for the passage of the Stewart B. McKinney Act and organizing for the Housing Now! march, which to this day is one of the largest to ever take place in Washington, DC.

This bumper sticker urged voters in 1984 to support Initiative 17, which established a right to shelter in Washington, DC. The initiative passed overwhelmingly.

Stewart B. McKinney Act

CCNV’s ongoing protests at the White House and the US Capitol throughout the 1980s raised the national awareness of homelessness and ultimately helped shape federal policy. Shortly after turning over the Federal City Shelter to CCNV, in 1987 President Reagan signed the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act into law. The landmark legislation provided an influx of federal funding for homeless social services across the country. It has been amended and reauthorized several times, but it remains the most consequential federal commitment to supporting homeless social services. A section of the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act next to a pen used to sign it into law and a photo of Mitch Snyder shaking the hand of Jim Wright, the Speaker of the House at the time. The Stewart B. McKinney act provided federal money for homeless shelters and remains the most significant piece of legislation establishing our present-day federal policies pertaining to homelessness and sources of funding for social services.

Housing Now!

CCNV demonstrated the peak of its influence in 1989 as it worked with the National Coalition for the Homeless to organize the Housing Now! March on Washington, DC. Held on October 7,1989, in response to the Reagan administration’s $25 billion cuts to the Federal housing budget, over a half million people descended on Washington demanding an end to homelessness.

Mitch Snyder and Carol Fennelly are pictured on the east steps of the Capitol during the Housing Now! march.

1989-1993: The End of an Era

The Death of Mitch Snyder

Tragedy struck on July 3, 1990 when Mitch Snyder’s body was found in the CCNV shelter, having allegedly committed suicide. He was 46. In the months before his death, Snyder had expressed frustration at the lack of public interest in homelessness – less than a year after the success of the Housing Now! march. His death marked a turning point in the homeless advocacy movement locally and nationally and led to growing tensions within CCNV. Initiative 17 expired and was not renewed by District voters in 1991, and the city budget dedicated to services for the homeless sharply decreased in the early ‘90s, with cuts as high as $4 million in 1994.These setbacks signaled the emergence of a backlash against the homeless advocacy movement.

Mitch Snyder’s Funeral Procession

On July 10, 1990 Mitch Snyder’s funeral casket and mourners processed down Pennsylvania Avenue in a black, horse-drawn carriage. A white, riderless horse led the procession of thousands of mourners.

Campaign to Save Initiative 17

One of the last major battles Carol Fennelly fought while at CCNV was to save Initiative 17. Unfortunately, only four months after the death of Mitch Snyder, voters defeated Referendum 005, which would have continued the Right to Shelter. Fennelly continued to run the shelter for four more years until CCNV forced her out in 1994, shed its activist identity, and began to see its role as a social service provider. Fennely turned her attention to help families of prisoners maintain bonds with their loved ones at the non-profit Hope House, where she still works to this day.

The End of an Era

CCNV’s first two decades were characterized by the community’s determined radical activism, which was at times abrasive and confrontational, but ultimately extraordinarily impactful. Their efforts continue to inspire the communities experiencing homelessness today. By identifying poverty as a form of violence, the fight against homelessness was transformed into an issue of human rights that reached the forefront of a national conversation. CCNV’s protests, while radical, were non-violent and worked to humanize the homeless community for which it fought. However, despite the progress made during this pivotal moment in history, poverty continues to be a pervasive issue, particularly in the nation’s capital.

Homelessness in America - Mary Ellen Hombs

In 1982, co-authors Mary Ellen Hombs and Mitch Snyder published one of the country’s first books on the 1980s homeless crisis drawing primarily on Hombs extensive research. Hombs, raised in a liberal Episcopalian family, moved throughout her childhood as her father served in the Air Force as a dentist. As an undergraduate student at George Washington University, Hombs helped found CCNV in 1970. Through her participation in CCNV and her opposition to the Vietnam War, she became a committed “Christian anarchist.” She helped establish the Zacchaeus Community Kitchen and would become CCNV’s chief researcher, writer and manager of the group’s finances. Like others in the group in the 1970s and 1980s, Hombs lived in poverty in part to avoid paying taxes that would go towards military expenditures.

Radical Discipleship - Carol Fennelly

Carol Fennelly fasted for 42 days on liquids during the Corpus Christi campaign. Fennelly explained what moved her to act, “We have taken all the riches of our people and we’ve invested them into these weapons…Isn’t what we’ve done is build a golden calf, and don’t we bow down to it? And now we are actually calling them God!”

Carol Fennelly was raised in a working-class family of Latter Day Saints in Southern California. After graduating from high school, she moved into a commune and had two children, Sunshine and Shamas, with her partner. After Shamas was born, Fennelly had an intense conversion experience through which she realized, “God has very special plans for me.” Fennelly began a class in radical discipleship, separated from her partner, and eventually moved with her children to Washington, DC to join the Sojourners Community and then CCNV during the Fairmount Shelter campaign. Her children would be an integral part of the Euclid House Community, and Fennelly became the point-person for media relations and the group’s most effective lobbyist.

Leadership

CCNV cultivated a style of resistance evident in its leadership. Mitch Snyder (center), Mary Ellen Hombs (left), and Harold Moss (second from right) – propelled the group’s collective action with their steadfast commitment to the movement to end homelessness.

Curated by: Dan Kerr, Hannah Byrne, Maren Orchard

Contributing Researchers: Jonathan Amthor, Ava Dennis, Hannah Duling, Randi Epstein, Nathaniel Keller, Daniel Kerr, Kathleen McCall, Michael Mottola, Joshua O’Steen, Daniel Pepper, Suzanne Pranger, Sophie Rapley, Amanda Robic, Jacob Tananbaum

Special Thanks to: The George Washington University Special Collections Research Center, Leah Richardson, Kierra Verdun, Rachel Trent, Chelsea Shapiro, and Caroline Willauer

Digital Exhibit by: Kimberly Oliver