Table of Contents

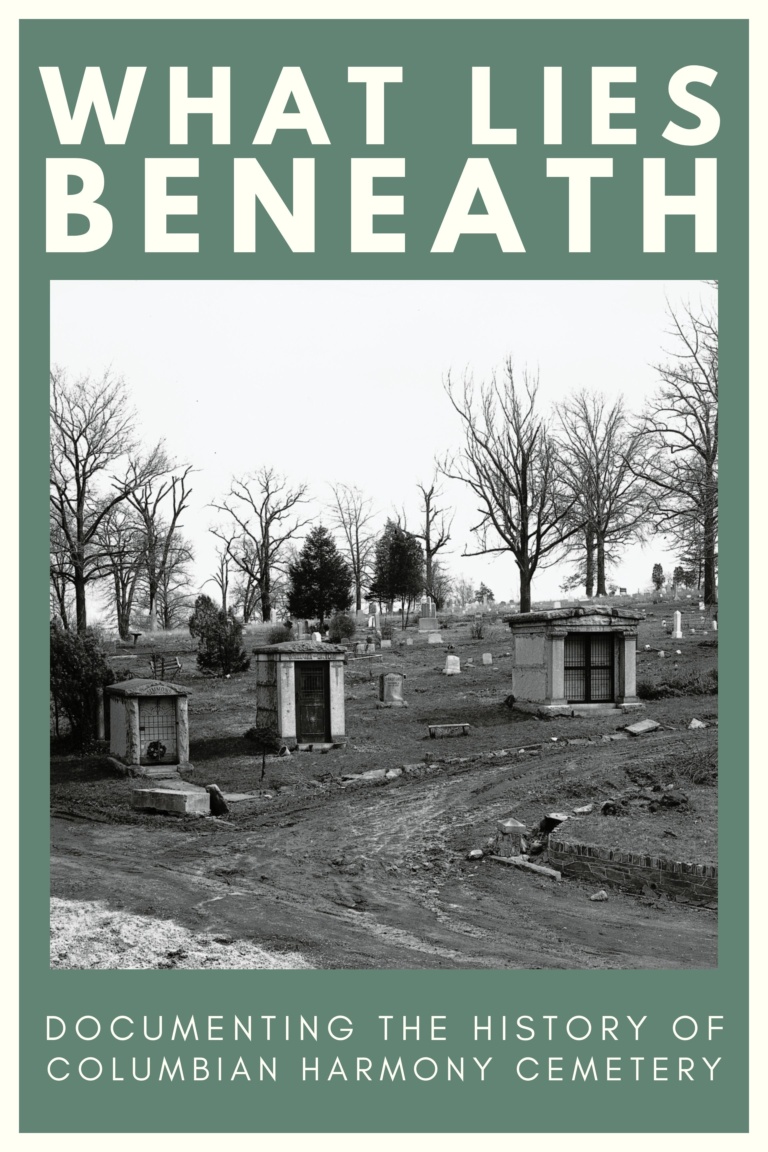

The Columbian Harmony Cemetery was an African American burial ground founded in the early nineteenth century in Washington DC. Today, Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood Metro Station and residential and retail complexes occupy the space where 37,000 Washingtonians were laid to rest.

How and why was the Columbian Harmony Cemetery erased from the city’s landscape? How has the physical space changed over time? And how do we memorialize the thousands of individuals who were interred at the Cemetery?

Remembering the Columbian Harmony Cemetery is a first step toward honoring the site’s history and restoring justice to the descendants of the thousands who were buried there.

The Columbian Harmony Society, 1825-1829

The Columbian Harmony Society faced financial difficulties from its conception. It had no long-term financial plan, was not able to properly maintain the cemetery, and sold off land as a short-term solution, leading it to run out of space. The Society’s financial plan depended on the sale of grave lots, and as the cemetery filled up, it had no way to fund the cemetery. Very few records exist from Columbian Harmony Cemetery, and there are decades of gaps. This timeline attempts to recount the known records to understand as much of the history as possible. It is constructed from information documented by Paul Sluby and Stanton Wormley, and newspaper articles from the time period.

1825

The Columbian Harmony Society is founded as a mutual aid society to benefit and support the African American community in Washington DC. (The goals of a mutual aid society are to support members in times of hardship and create a community of fellowship among them.)

“By no other motive than those which bind man by the tender ties of fellowship and mortal duty and believing that much good may result by uniting ourselves into a society.”

1828

The society opens the Harmoneon Cemetery on square 475 of Washington City just south of Florida Avenue, as the first African American cemetery in Washington DC The cemetery filled up quickly. However, this tract of land is too small and the Society soon makes plans to relocate.

1856

A DC ordinance requires all cemeteries south of Florida Avenue to relocate. The Society had planned to move to a larger space, but it is now forced to act immediately.

1857

Columbian Harmony Cemetery opens at its new location at Rhode Island Avenue and Brentwood Road. It has initially purchased 17 acres, a massive expansion from its previous tract of only 1.3 acres. (The cemetery will later expand to roughly 34 acres).

From Busy to Bought, 1880-1950s

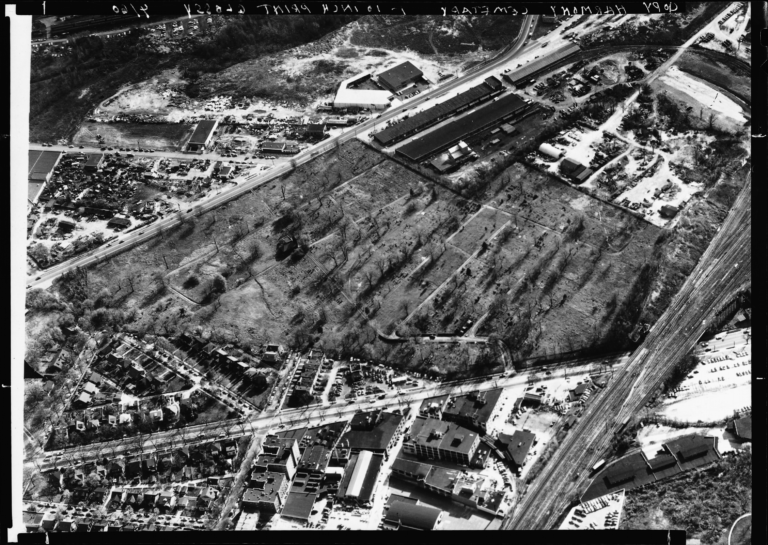

An aerial view of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery at the Rhode Island Avenue Site. The cemetery was situated between Rhode Island Avenue and Brentwood Road, N.E. Date unknown. (Scan courtesy of DC History Center)

1885

The Columbian Harmony Association is formed to control and manage the cemetery; however, John F. Cook, the trustee of the cemetery, remains in control of business operations. He reorganizes and incorporates the Columbian Harmony Association into the Columbian Harmony Society.

1886

Lot owners file a lawsuit against the Columbian Harmony Society, citing financial mismanagement. They argue that the cemetery is being maintained only by those who own cemetery plots and that there is no management of the cemetery by the Society. Meanwhile, the Society seeks to expand the cemetery grounds because of a rapid increase in burials; more land is needed to accommodate the community’s needs. The DC Commissioners oppose the expansion, citing local laws regarding cemetery location and development.

1889

In a meeting with the lot owners, the secretary of the Columbian Harmony Society states that, because this is a private society, he does not need to provide any financial records or proof of its spending; it only has to allow the owners to bury people in the plots they purchased.

May 30, 1890

During the annual Decoration Day observation at the cemetery, lot owners are appalled that the condition of the cemetery has not improved and in fact has continued to deteriorate. Lot owners have formed a committee to investigate the management and organization of the Society and cemetery.

1899

The Columbian Harmony Society applies for tax-exempt status but is denied by the DC. Commissioners. Plots that have been sold for burial are not taxed but all other lands in the cemetery are deemed taxable. To ensure the cemetery’s survival, the Society will have to start selling off land that had not yet been used for burials.

1903

The Columbian Harmony Society sells off part of the cemetery property for $19,460.87.

1920s

The area around the cemetery begins to be developed. Racially restrictive covenants reserve much of the new housing for white buyers only.

Map of Columbian Harmony Cemetery demonstrating the rise of racially restrictive covenants near the cemetery. The red denotes an area with one or more racially restrictive covenant.

1923

The Columbian Harmony Society sells off another piece of the cemetery, for $20,636.25.

1928

The Columbian Harmony Society sells an additional section of its land, for $14,501.50.

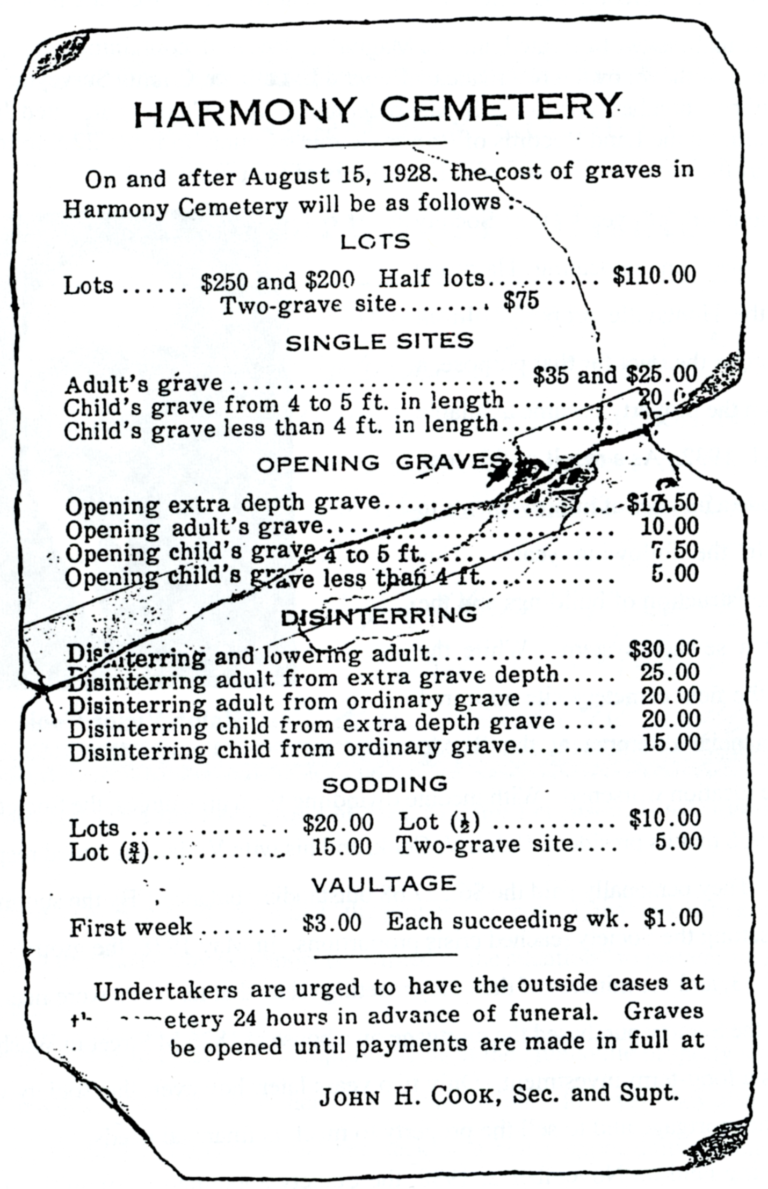

A surviving receipt from the late 1920s shows the internment costs at Harmony Cemetery. (Scan courtesy of DC History Center)

1929

Intending to relocate the cemetery, the Columbian Harmony Society purchases 44.75 acres called the Huntsville, in Prince George’s County Maryland, tract for $18,000. This is meant to be a permanent solution to the Society’s financial issues. However, the land is very expensive, and the Society has had to borrow $10,000 to pay for improvements to the site.

1940

The Society considers selling the Huntsville tract at a loss, but it still maintains that purchasing a larger property and moving the cemetery would be the best way to solve its financial problems.

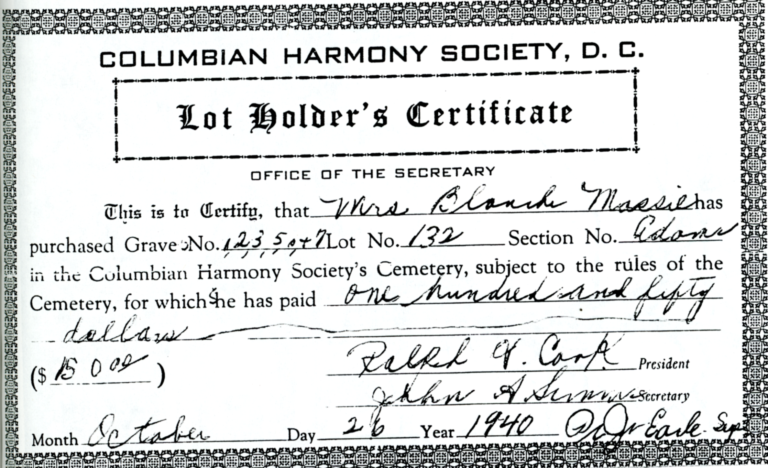

A Lot Holder Certificate from the Columbian Harmony Society. The certificate shows the purchase of several graves from Lot No. 132 for the price of one hundred and fifty dollars. The certificate was signed by the President and Secretary of the Columbian Harmony Society on October 26th, 1940. (Scan courtesy of DC History Center)

1949

The lot owners agree that the cemetery needs help so they form the Lot and Grave Owners Association “for the mutual preservation of the right, title, and interests (including site and grave care) of the lot and grave owners in Columbian Harmony Cemetery.” The Lot and Grave Owners Association brings a lawsuit against Columbian Harmony Society and submits a petition with 344 signatures opposing the relocation. The suit is settled in 1952 with an agreement that any future sale must be approved by Congress or by court decree.

1950

The Society stops selling single gravesites and sells only burials in larger plots because it has run out of space.

1952

In response to complaints to the DC Health Department, the cemetery is charged with violating public health rules.

1953

The Society sells the Huntsville tract for $178,031, despite the cemetery’s need for more space. Relocation is estimated to cost $500,000.

Cemetery Removal, 1960s

1958

After several offers and negotiations, real estate investor Louis H. Bell buys the Columbian Harmony Cemetery and promises to fund the reverent and respectful relocation of all interments to National Harmony Memorial Park in Maryland. He pledges to designate a “Harmony Section” at the new location, and offers the Society board seats and a 25% stake in the new cemetery. About 37,000 graves need to be moved; this would be the largest cemetery relocation in DC history. The agreement with Bell does not require him to relocate the gravestones.

Photograph of the Gate House and surrounding area at Columbian Harmony Cemetery, dated 1959. (Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Photograph showing the grounds of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery at Rhode Island Avenue, dated 1959. (Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

1960

From May to November, burials are removed from Columbian Harmony Cemetery and reinterred at National Harmony Memorial Park. The DC Department of Health streamlines the process by issuing a single mass removal permit, rather than a permit for each individual interment, as has been the standard procedure. In 1982, a neighborhood resident recalled to the Washington Post that “they placed the bones in boxes the size of tissue boxes.”

Photograph of Louis. H. Bell, the real estate investor who bought the site of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery in the late 1950s. (Scan courtesy of DC History Center)

1962

In a ceremony featuring an address by the Dean of Howard University’s School of Religion, National Memorial Harmony Park is dedicated as the Columbian Harmony’s new home.

1965

Remains from two other African American burial grounds purchased by Louis Bell, Rosemont Cemetery in Southeast DC and Payne’s Cemetery in Northeast DC, are relocated to National Harmony in Maryland. Fletcher-Johnson Middle School would be built on the site of Payne’s Cemetery.

Modernization & Development, 1965-Present Day

How and why was the Columbian Harmony Cemetery erased from the city’s landscape? And what does that space look like now? Today, the site of what was DC’s largest African American cemetery is occupied by the Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood Metro station, taxpayer-supported retail and residential complexes Rhode-Island Row and Israel Senior Residences, and Home Depot. Most Washingtonians have no idea that they are riding the Metro, shopping, or living over land that was occupied by the city’s most significant Black burial ground.

1967

Louis Bell sells the former Columbian Harmony Cemetery property to the DC government for nearly $3.5 million. He had purchased it for $400,000. By this time, Bell has purchased at least three other Black cemeteries in DC—Woodlawn Cemetery (1961), Rosemont Cemetery (1965), and Payne’s Cemetery (ca. 1966-1968), which he also sells to the DC government for a large profit after receiving a blanket permit for the disinterment of thousands of burials. The city plans to build a section of an interstate highway on the former Columbian Harmony land, but meets resistance from DC residents and eventually abandons those plans in favor of constructing a subway system, the Metro.

1969

Louis Bell sells the Payne’s Cemetery tract to the DC government for approximately $1.5 million.

Early 1970s

The city sells 3.6 acres of the former Columbian Harmony Cemetery to Metro.

1976-1979

The city builds the Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood Metro Station and three years later, a parking lot for impounded vehicles. During construction, coffins, human remains, and cloth fragments are unearthed. Newspapers deem these discoveries a “surprise,” as it was thought that all 37,000 burials had been reinterred at National Harmony Cemetery in Landover, MD as promised by Bell.

1980s

The Columbian Harmony Society discovers that the relocation agreement did not cover memorials and monuments, such as the mausoleum and the chapel. In addition, based on the 1958 agreement, none of the original grave markers were retained for reinstallation at National Harmony Cemetery.

2012

Rhode Island Row, the residential and retail complex surrounding the Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood Metro station, is completed. Rhode Island Row’s receipt of federal funding requires an archaeological review of the area by the D.C. Office of Planning (DCOP). More coffin remnants, fragmentary human remains, and some loose markers and funerary hardware are recovered. All are given to a forensic anthropologist and then reburied at National Harmony.

2016

Visionary Square opens. It is also called the Israel Senior Residences Project, and is sponsored by Israel Baptist Church, Mission First Housing Group, and The Henson Development Company. The “vision” behind the residential complex is to provide affordable housing options to the seniors of the community. Due to the presence of remains at Rhode Island Row, DCOP requires a full survey of the property, which unearths still more coffin remnants, human remains, and funerary hardware. In the section of the former cemetery that is surveyed, 153 intact coffins, which still contain human remains, are excavated. These remains are reburied at National Harmony. The 153 reburials are marked with six plaques.

Memorialization

How can we remember, honor, and restore dignity to the 37,000 individuals who were buried at Columbian Harmony Cemetery, and begin to address the loss experienced by their descendants?

In 1981, Metro board member Jerry A. Moore, Jr. led an unveiling ceremony of a commemorative plaque recognizing the Rhode Island Ave-Brentwood Metro station as the former site of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery. A small, square, bronze commemorative plaque was set in a concrete wall facing the station exit. The plaque reads: “Former site of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery 1857-1959. Many distinguished black citizens, including Civil War veterans, were buried in this cemetery. These bodies now rest in the new National Harmony Memorial Park Cemetery in Maryland.” This is the only existing memorial to the Columbian Harmony Cemetery.

In 2016, Virginia state Senator Richard Stuart spotted headstones in the Potomac River along his property in King George County, Virginia. Stuart called in local historians and state officials to take a look. They discovered that, between 1960 and 1967, Columbian Harmony gravestones were sold and hauled off as erosion control rip-rap. A former owner of Stuart’s farm in Virginia had seen an ad —“free rip-rap for pick up” —and acquired several truckloads to build up his shoreline. He transported the headstones to his property and dumped them down the Potomac River bank to prevent his land from eroding into the river.

Headstones recovered from the Potomac River, currently on display at Caledon State Park

Virginia Governor Ralph Northam stepped in to help Stuart, and the state enlisted the nonprofit group, the History, Arts, and Science Action Network (HASAN), to remove as many headstones from the Potomac River as possible. Historians Kelley Fanto Deetz and Lex Musta, along with filmmaker Justin Fornal, launched Project Harmony, an initiative to recover and repatriate the displaced and desecrated headstones and to work with descendants to create memorials. Project Harmony has recovered over fifty headstones from the Potomac River, as well as pieces of the original cemetery’s mausoleum and its chapel. In 2020-2021, the headstones were temporarily displayed at Caledon State Park, which is adjacent to the property where they were found. Musta calls this work “restorative justice” and has been researching the names on headstones as they emerge from the river.

Project Harmony

Project Harmony works with a large descendant community, the Sons and Daughters of Harmony Cemetery. Founded in 2020, the goals of the descendant community include memorialization, education, restoration, and connection.

“Our work is dedicated to funding and delivering an honorable living memorial wall at the site where the headstones were dumped as rip rap in the 1960s, returning intact headstones to a memorial park near a site where their bodies are interred, and to inspire new generations of Virginia, DC, and Maryland youth by the example of the lives of these heroic Liberation Community members in DC…”

Sons and Daughters of Harmony Cemetery

Plans are afoot to create memorials to the Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Virginia and Maryland. The state of Virginia has allocated $4 million toward the removal of headstones from the Potomac River and to the creation of a memorial. Discussions with Maryland Governor Larry Hogan have led to plans to send repatriated headstones to National Harmony Memorial Park in Maryland and to create a memorial garden at the cemetery’s entrance. Plans are also being made for the “Harmony Living Shoreline Memorial” to be located in the Potomac River along the shoreline where the headstones were discovered.Thousands of gravestones that cannot be found or removed will remain in this location.

Say Their Names

“... even the Black souls who have transitioned do not have their corpses dignified well after they are gone.”

-Morgan Jerkins

Approximately 37,000 individuals were buried at Columbian Harmony Cemetery, making it one of the most active cemeteries in all of Washington DC. Due to the cemetery’s removal and subsequent loss of gravemarkers, many of those souls have lost their resting place.

The removal of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery is part of a larger history of the desecration of African American cemeteries and the erasure of Black history across the city and the nation. Naming individuals interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery—and remembering their stories—celebrates their significant contributions and preserves their legacy. Each vignette below represents one of these 37,000 stories.

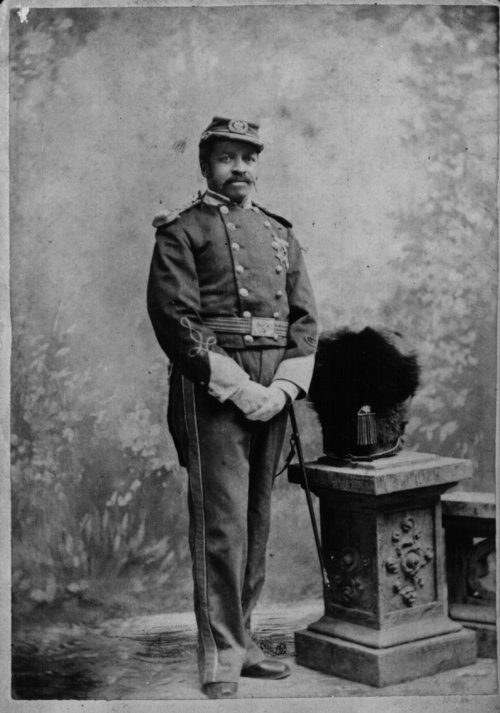

Christian Fleetwood

Portrait of Christian Fleetwood, posing in his post-Civil War, instructor uniform for a battalion of Black DC National Guardsmen. During the Civil War, Sergeant Major was the highest rank allowed to a Black Soldier(Library of Cong. ress, Prints and Photographs Division)

During the course of the Civil War, 25 Black Americans received the Medal of Honor; over half for the Battle of New Market Heights in September of 1864. One of these men was Christian Abraham Fleetwood. Born in Baltimore to free Black citizens, Fleetwood graduated from Ashmun Institute, later known as Lincoln University whereupon he and several other men established the Lyceum Observer in Baltimore. It was one of the first black newspapers in the South.

Fleetwood was part of the first wave of Black men to enlist in the Union Army after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, joining the 4th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Fleetwood quickly rose to the rank of Sergeant Major, the highest rank allowed for a Black soldier at the time. On September 29, 1864, the 4th USCT regiment was ordered to charge on Confederate fortifications on the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia. Here, Fleetwood earned the Medal of Honor when he seized the colors, after two flag bearers had been shot down, and bore them nobly through the fight.

Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood’s medal of honor, received during the Battle of New Market Heights in September of 1864 for having “Saved the regimental colors after eleven of the twelve color guards had been shot down around it. (Division of the History of Technology, Armed Forces History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

After the war, Fleetwood served in several government positions with the Freedmen’s Bank and the War Department in Washington D.C. Inspired by his military career, he organized a battalion of Black D.C. National Guardsmen and the Colored High School Cadet Corps of the District of Columbia. Fleetwood died of heart failure on September 28t, 1914, and was interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery. His original headstone has not been recovered; however, a replacement has been installed at National Harmony Memorial Park.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley

Portrait of Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley in 1861, taken during her time as a dressmaker to Mary Todd Lincoln. (Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University)

In February 1818, in Dinwiddie, Virginia, Elizabeth Keckley was born into slavery. Her mother, Anges Hobbs, was enslaved by Armistead and Mary Burwell, who later loaned Keckley to their eldest son Robert and his wife Margaret. She suffered greatly under Margaret’s rules and was sexually assaulted by a prominent white man of the community, Alexander M. Kirkland. Keckley bore his son.

Facing financial hardship, the Burwells moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1847, where Keckley lived with them for twelve years. There she mingled with the free Black community and formed connections with the white community as a seamstress. Keckley eventually bought her and her son’s freedom for $1,200 in November of 1855.

In 1860, Keckley moved to Washington D.C., supporting herself as a seamstress and dressmaker. It is through this business that Keckley met Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckley served as the First Lady’s dressmaker for four years during her husband’s presidency and for many years after continued to design Lincoln’s dresses. In August 1862, Keckley founded the Contraband Relief Association, which distributed clothing, food, and shelter to refugees from slavery.

First Lady Mary Lincoln’s purple velvet skirt and bodice trimmed with lace and pearls, made by Elizabeth Keckly during the Washington winter social season of 1861-1862.” (Division of Political and Military History, Nation Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

In May of 1907, Keckley died in Washington DC and was interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery. It is unclear if Keckley’s body was among those moved to Maryland in 1960. Her headstone has not been recovered.

“Perhaps the most poignant illustration of the different fates of these two women is found in their final resting places. While Mary Lincoln lies buried in Springfield [Illinois] in a vault with her husband and sons, Elizabeth Keckley's remains have disappeared. In the 1960s, a developer paved over the Harmony Cemetery in Washington where Lizzy was buried, and when the graves were moved to a new cemetery, her unclaimed remains were placed in an unmarked grave—like those of her mother… and son.”

-Sharon Barnes

Osborn Perry Anderson

Portrait of Osborne Perry Anderson, sole survivor of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. (West Virginia Archives & History)

Osborne Perry Anderson was born free in West Fallowfield, Pennsylvania, in 1830. Educated at Oberlin College in Ohio, Anderson eventually moved to Chatham, Canada, to establish a print shop. In 1858, Anderson met John Brown, who shared his plans for a revolution of enslaved peoples in America. This greatly appealed to Anderson. Because of his writing skills, he was appointed the recording secretary at Brown’s meetings, and eventually promoted to a member of Brown’s planned provisional congress.

With Brown, Anderson and 22 others planned an assault on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with the hope of inciting a slave rebellion. The raid took place October 16-18, 1859. Anderson was the only surviving member of Brown’s raiders. He fled to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Anderson was helped by a Samaritan believed to have been William C. Goodridge, a conductor on the underground railroad. Anderson made his way back to Canada, but during the Civil War, he became a noncommissioned officer of the Union Army.

Anderson died a pauper of tuberculosis in Washington DC in 1872, and was interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery. His headstone has not been recovered.

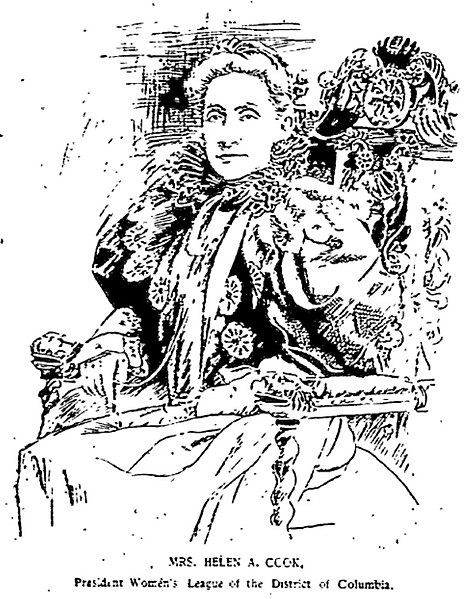

Helen Appo Cook

Illustration of Helen Appo Cook in June of 1898 during her presidency of the Colored Women’s League of the District of Columbia. This organization merged with the National Federation of Afro-American Women to form the National Association of Colored Women. (The Colored American Newspaper of Washington, DC)

Helen Appo Cook was born in New York state in 1837 to William Appo, a prominent musician, and Elizabeth Brady Appo, a milliner. Not much is known about Cook’s upbringing; however, it is believed that she was highly educated and a talented organist. Through her mother, young Helen Appo became involved with the women’s rights movement. As an adult, she attended the first national suffrage convention, held in January 1869 in Washington, DC. In a letter, Appo expressed disappointment in this convention, which discussed suffrage only for newly emancipated men, not for women.

At an unknown date, Helen Appo married John Francis Cook, Jr., a trustee of Columbian Harmony Cemetery, with whom she would have five children. The Cook family was one of the most prominent and wealthy Black families in the city at the time. Cook later became the first president of DC’s Colored Women’s League, a role she would fill for over a decade.

Cook traveled to Boston in 1895, where she was elected Vice-President of the First National Conference of Colored Women of America, held in Boston. This conference led to the creation of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, which merged with the Colored Women’s League to form the National Association of Colored Women. In subsequent years, Cook continued to fight for both gender and racial equality, joining leaders such as W.E.B. Du Bois in campaigning for justice. She condemned white women leaders, including Susan B. Anthony, for prioritizing white women’s advancement at the expense of Black women.

On November 20, 1913, Cook died from pneumonia and heart failure at her family residence. She was buried in Columbian Harmony Cemetery alongside her husband and other Cook family members. Her remains were among those disinterred during the cemetery’s removal.

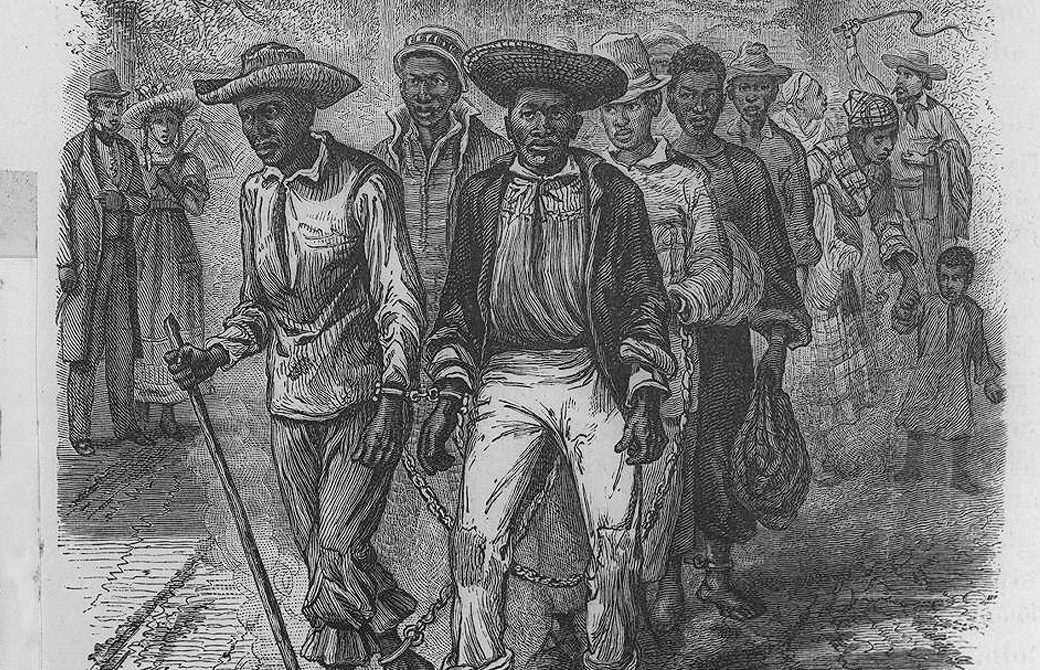

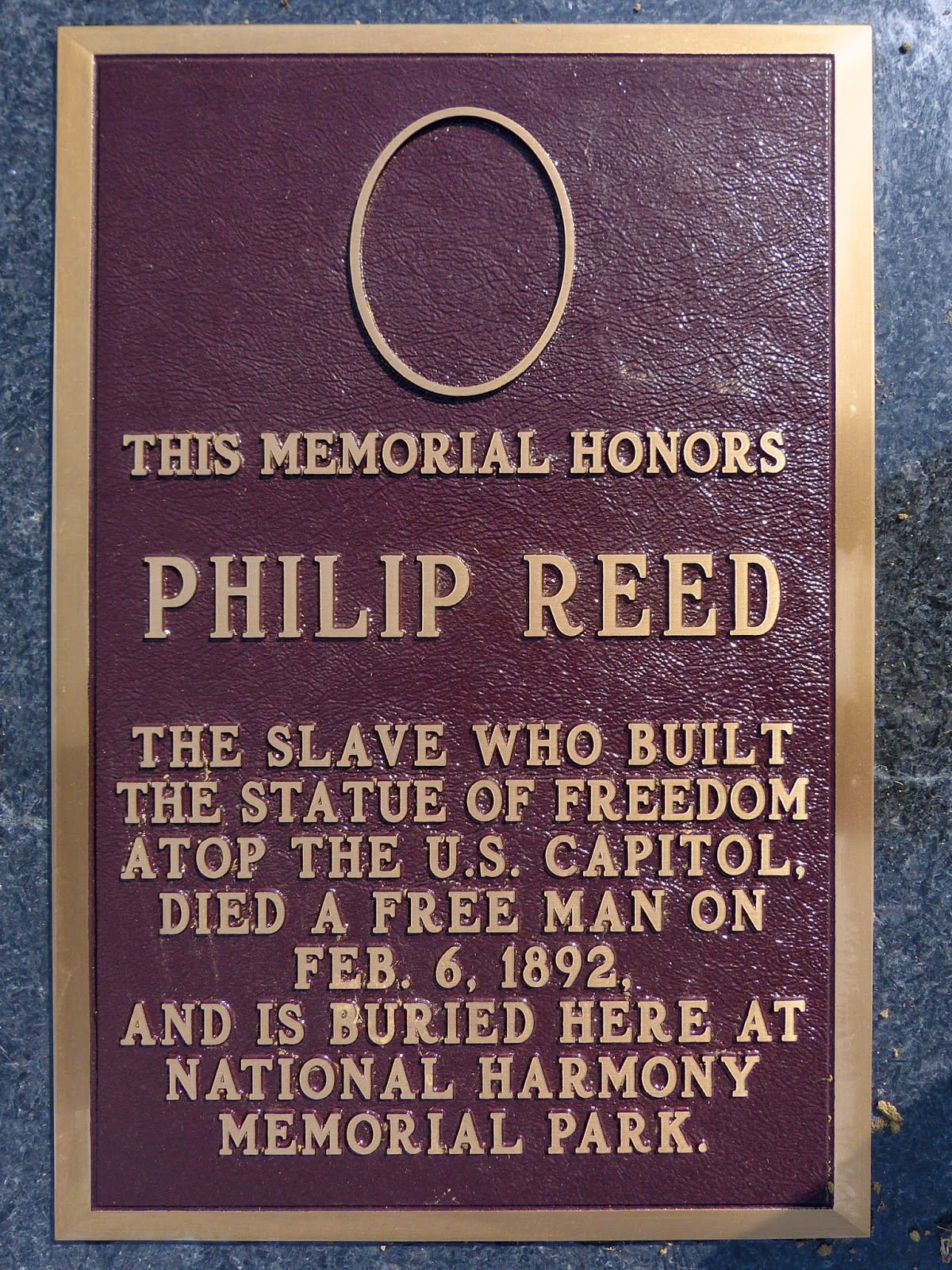

Philip Reid/Reed

A 1815 etching of enslaved men who worked to build the Capitol. Philip Reed was one of these enslaved men and the only one who worked on the Statue of Freedom.

Philip Reid was born enslaved in Charleston, South Carolina, around 1820. Purchased as a youth by Clark Mills, an ironworker, Reid quickly became an integral part of Mills’ construction team due to his skills as a craftsman. In 1848 Mills’ team, including Reid, received its first major project, an equestrian statue of former President Andrew Jackson to be placed in Lafayette Square, across from the White House. After winning the bid, Mills moved Reid and the rest of the workmen to the nation’s capital, creating a temporary foundry south of the White House. There, they cast six versions of the equestrian statue, finally completing the work in 1852.

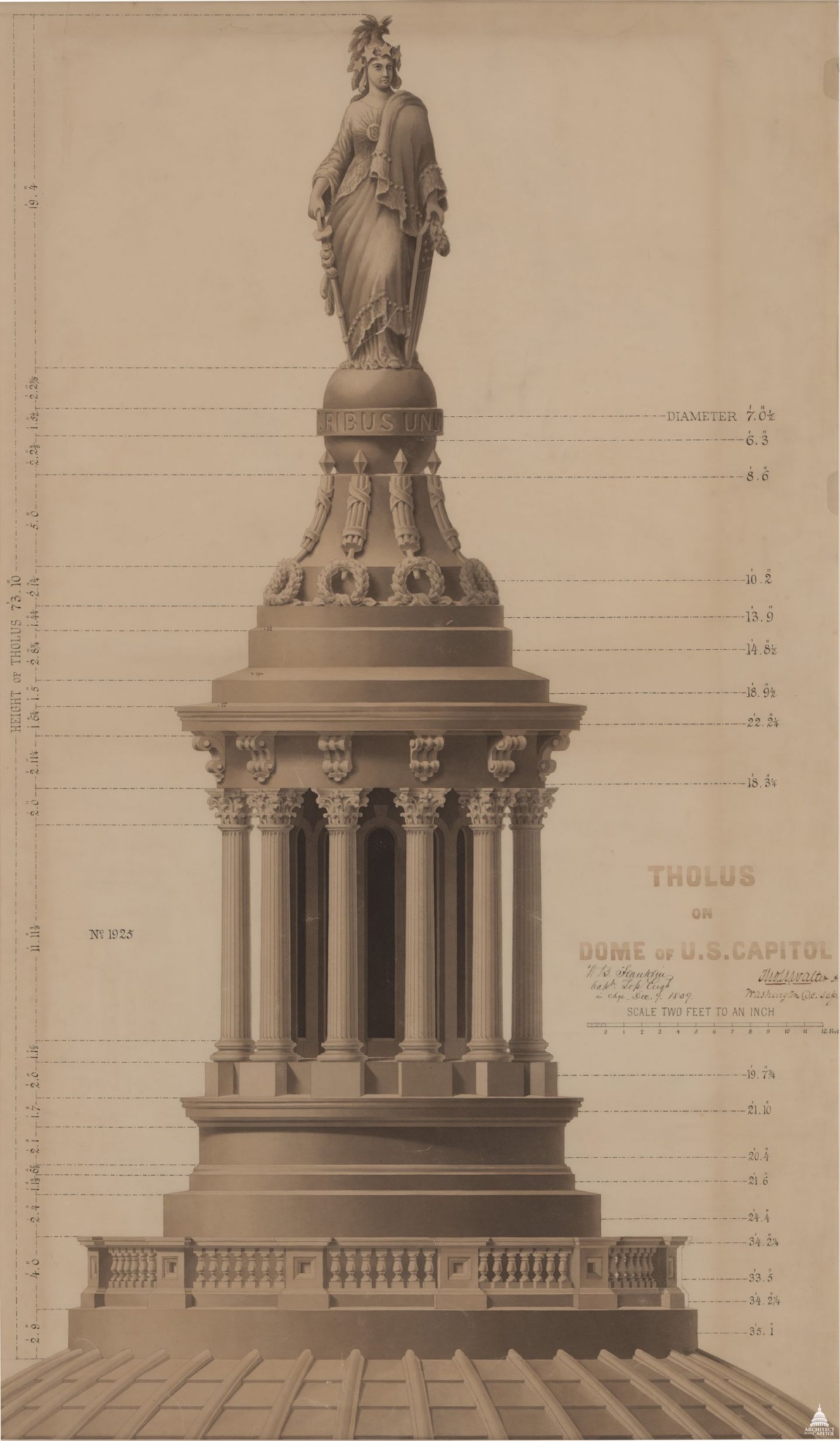

The success of the Jackson project made Mills the leading candidate for creating the Statue of Freedom, to be placed atop the U.S. Capitol in May of 1860. Reid was integral to the casting process of the statue, as the plaster mold had arrived bolted and unusable. Reid engineered a rig to unseal the mold and allowed the casting to begin June of the same year. Reid worked on the project with the other laborers from July 1, 1860, until May 16, 1861. During this time Reid was listed as a “laborer” in Mills’ monthly expense report, receiving $1.25 a day for his work. He is the only known enslaved person to have worked on the statue, although other enslaved workers were part of the construction crew.

1859 drawing by Thomas Walter of the Tholos of the Capitol Dome and the Statue of Freedom. The statue was put into place into place on December 2, 1863.

On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, leading Clark Mills to receive $350.40 from the government as compensation for Reid’s freedom. Following emancipation, Reid changed the spelling of his name to Reed. Little is known about Reed’s life following the Civil War, other than that he remained in DC and worked as a plasterer. According to the 1870 Census, he was married and had a two-year-old son.

Reed died on February 6, 1892, and was buried in Graceland Cemetery, in what became known as the Carver Langston neighborhood of Northeast DC. The cemetery was forcibly closed due to financial mismanagement in 1894, and a year later Reed’s remains were moved to Columbian Harmony Cemetery. They were disinterred once again when Columbian closed, but this time reburied without a marker. Reed’s original gravestone has not been recovered.

Memorial plaque honoring Philip Reed placed at National Harmony Memorial Park, the new resting place of Reed after disinterment. (Architect of the Capitol)

“...Much credit is due [to Philip Reed] for... modeling and casting America's superb Statue of Freedom, which kisses the first rays of the aurora of the rising sun as they appear upon the apex of the Capitol's wonderful dome."

— William A. Cox. Congressional Record. 1928

About the Authors

Katlyn Calamito, Amanda Gallagher, Rebecca Kaliff, and Alexis Zilen are Public History Graduate students at American University in Washington, DC.

Prologue DC

Prologue DC’s team is Mara Cherkasky and Sarah Shoenfeld, experienced historians, researchers, writers, speakers, and exhibit planners. They believe that understanding our city’s past is key to understanding and appreciating its unique 21st century culture. Enslaved and free African Americans, immigrants, wealthy landholders, prominent politicians, and many others—all of them built Washington. In telling their stories, Prologue presents history that is relevant, educational, and sometimes entertaining. Prologue’s online public history project Mapping Segregation in Washington DC , has been revealing particularly important stories since 2014.

Resources

The removal of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery from the District’s landscape is part of a larger history of the desecration of African American cemeteries and spaces, and the erasure of Black history in DC. Please explore the resources below to learn more about HASAN’s Project Harmony, African American burial grounds in DC, and the work of Prologue DC and others in documenting the city’s historic Black communities and what happened to them.

Columbian Harmony Cemetery

Chronicling America « Library of Congress

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN: Cemeteries in the Nation’s Capital

How headstones from a historic Black DC cemetery wound up along the Potomac River in Virginia

Sluby, Paul E. Records of the Columbian Harmony Cemetery , Washington, D.C. Columbian Harmony Society: January 1, 1993.

Sluby, Paul E. and Stanton Lawrence Wormley. History of the Columbian Harmony Society and of Harmony Cemetery, Washington, D.C. The Society: 2001.

Other Black Cemeteries in DC

DC's Historic Black Communities

Mapping Segregation in Washington DC

- Historic African American Communities in the Washington Metropolitan Area

- Displacement from Meridian Hill

- How Racially Restricted Housing Shaped Ward 4

- The Demise of Ward 4’s Historic African American Communities

- Brightwood’s Historic African American Community

- Mapping Spatial Violence: dispossession, public housing and “new communities”

Barry Farm Dwellings: A Struggle for Civil Rights in Southeast DC

Fort Reno: Growth and Displacement