Harm reduction acknowledges that drug use is here to stay, that drug use has risks, and that the best measures to address it are ones that reduce harm and empower people to improve their quality of life in any way — any movement toward positive change. It’s rooted in activism, advocacy, and social justice. It’s for the communities they serve, by the communities they serve. It’s more than a set of programs. It’s a community and network of people — for the people/by the people — who live by a harm reductionist philosophy.

By mobilizing around the dire need to protect oneself and community to reduce the risk associated with injecting drug use during the HIV/AIDs epidemic, “harm reduction” was born. There was a keen awareness that the government, care providers, and society didn’t care about the injection drug user population (or LGBTQ+ folks). Those who were at the highest risk of HIV/AIDS, were left by the state to die. Impacted people mobilized on the ground to teach each other how to protect themselves and distribute any kind of resources attainable. They grew to actively urge government entities, public health officials, and the average person to consider, implement, and fund a variety of models for approaching drugs that aren’t solely grounded in abstinence-based and prohibitionist values. It was a radical, activist movement when people who use drugs (PWUD) started to demand that governing bodies see PWUD as people who were not only not being served by existing conditions, but actively harmed.

The origins of harm reduction spawned from a radical social movement that’s more than the set of strategies and resources (like opioid overdose reversal drug distribution and syringe exchange). Harm reduction challenges how society and policymakers conceptualize certain drugs and populations of people using those drugs.

While groups like the Young Lords Party and Black Panther Party were already organizing community-based harm reduction health-motivated direct actions and community support in the 1970s, it wasn’t formally recognized as a public health model until the 1980s. In the early 80s a harm reduction model was implemented in the Netherlands as harmful drug use and the comorbidity with HIV/AIDS was becoming more prevalent (notably, the demographic of PWUD widened). The existing prohibitionist model was not structurally sustainable and became unpopular with the public. To combat the growing health concerns, the Netherlands expanded (the already existing) needle exchange and distribution programs.

In the United States and Canada, organizers, advocates, communities, and renegade care-providers were already opposing legal restrictions on drugs and the criminalization, marginalization, and oppression of PWUD prior to the 80s (and before the “War on Drugs” was formally declared by Richard Nixon). When the HIV/AIDS epidemic worsened and started to impact more people, grassroots harm reduction communities started to organize with LGBTQ+ groups to save each other’s lives. If the government wasn’t going to help, then the people most impacted would help themselves.

Harm reduction started to gain traction out of necessity. The official terming of this approach can be traced to Russel Newcombe, a research psychologist, who published an article using “harm reduction” to describe Allan Parry’s work with a risk reduction clinical syringe exchange service based on the Dutch programs in Liverpool in 1986 (but please note that people were already practicing risk reduction education and techniques prior to this).

Communities were organizing to save themselves and their peers by teaching people who inject drugs to clean their needles with bleach and resist sharing when they could. Meanwhile, the local and federal government (which had a different socio-political landscape and history of strict prohibition and criminalization of Black and working class PWUD than the Netherlands) stumbled to find the legal support to implement needle exchange programs. Despite the plethora of evidence from scientific studies proving the multitude of social, societal, and health benefits that syringe exchanges and safe consumption sites offer, opposition to needle programs made implementation difficult. Driven primarily by state and federal legislature, drug-user stigma, misinformation campaigns, and existing punitive systems against PWUD — needle distribution has been fragmented from the start and is still divided as of the time of writing.

Note that these needle exchange programs offer more than sterile needles and syringes. These community-based programs can also provide referrals to substance use disorder treatment programs and other social and mental health care services, health screenings, 1-1 peer support, treatment for hepatitis and HIV, education about overdose prevention and safer injection practices, vaccinations, and beyond (services vary by site). According to many studies, major health organizations, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), these programs can help people reduce the harm of their drug use, stop using drugs, reduce infections, reduce drug overdoses, are cost effective and do not lead to more crime and/or drugs use.

Safe consumption sites (SCS or harm reduction centers) offer another technique and space for drug users. In July 2021, Rhode Island was the first state in the United States to legally authorize a two-year pilot drug consumption space, harm reduction center, and program. In November of 2021, New York City authorized two supervised injection sites in Manhattan that have already been saving hundreds of lives (writing in July 2022). DecrimPovertyDC is Washington, DC’s coalition to bring a overdose prevention site (and other harm reduction measures) to the District.

Despite decades of evidence, stigma and legal barriers still restrict access to the creation, funding, and utilization of these needle exchanges and safe consumptions sites in the United States. From the beginning, people running needle exchange services operated under illegal conditions via community organizing. Exchanges eventually gained funding through private and local means. In 1989, Congress voted that Federal money would not support needle programs and a decade later, despite plenty of evidence depicting the positive effects of these programs, the Clinton administration refused to lift the ban as they succumbed to drug fearmongering. Needle exchange and federal support has flipped a couple times under the Obama administration and the ban was partially lifted in 2016. While it was still federal law to prohibit the use of federal funds to purchase sterile needles or syringes, the funds could be used to pay for other aspects of needle exchange programs. In July 2021, the House Appropriations Committee approved a funding bill for 2022 that will allocate five times more money to harm reduction resources than the previous year that will also expand syringe service programs. It’s vital to understand that a presidential administration or government support of “harm reduction” doesn’t always align with on-the-ground and traditional understanding of the movement, philosophies, and implementations.

[For more information on needle exchange programs see: https://www.aclu.org/fact-sheet/needle-exchange-programs-promote-public-safety]

Practices and programs carried out by harm reductionists exceed needle exchange programs and safe consumption sites. Again, it is rooted in bottom-up community led efforts to address any gaps and structures of harm that governments and medical providers have caused and/or neglected. It was born from the struggle against ineffective, violent, punitive, moral models of “addiction”; it rose from health injustices and disparities. And it’s not just for people who use drugs. These principles, commitments, advocacy, activism, and services can be applied to unhoused people, sex workers, sex, and many other behaviors that impact people from every walk of life.

Harm reduction is liberatory accountability public health compassionate justice non-judgmental

It’s about liberatory, accountable, community driven, public health as social justice. Harm reduction is understood to be addressing the reality of harmful behaviors while creating realistic approaches to reduce any of that harm.

Harm reductionists are deeply committed to direct, on-the-ground outreach by providing resources, referrals, and information to communities and individuals who want it. Many harm reduction organizations also tackle the structural issues that create racialized, violent, problematic, and ineffective policies and conditions that PWUD navigate today. Again, this one of many all-encompassing commitments to advancing the rights, safety, and autonomy of the people they serve.

Other broad medical and system-focused key points and issues affiliated with harm reduction are implementing medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and decriminalization of all drugs.

The medicalization of “addiction” is a direct response and alternative model from the criminal model of treating the complex and multifaceted phenomenon of drug use. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), drug addiction is a “chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain. It is considered both a complex brain disorder and a mental illness.” This framework of addiction is bio-medicalized, identified in the body, and rendered legible through behaviors. The limits of this biomedical model will be addressed later.

But first, it must be known that medicalization vs criminalization of chaotic drug use is written along racial and classed lines — what’s considered a medicine or a diseased drug problem for some people (like middle class white folks) is a criminal activity for others (like Black, Latinx, and working-class white people). The push for medicalized narrative about drugs and people who use in the United States is historically drawn along theses racialized lines.

On route to the bio-medicalized understanding (rather than a purely moral version) of drug addictions, in 1965, Vincent Dole (researcher for New York City Research Council’s Committee of Narcotics) and Marie Nyswander (psychiatrist at Lexington Narcotic Farm – the addiction treatment penitentiary and failed site of drug research) conducted studies with methadone as an opioid-replacement and concluded that addiction is not a personality defect but a biological condition and physical disease.

Methadone is a synthetic opioid developed in Germany during World war II to relieve pain that became commonly used to treat substance use disorders and dependencies. Methadone is one of several medication assisted treatments (MAT) used to relieve withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings to opioids. Others include buprenorphine (opioid partial agonist used for opioid use disorders) and naltrexone (opioid blocker used for opioid use disorders and alcohol use disorders). Another key harm reduction drug development is naloxone (commonly known by the brand name for the nasal spray, Narcan) — this lifesaving drug reverses an opioid overdose. And great news! Naloxone cannot be misused, has very few rare side effects, and won’t cause harm if it’s administered to someone without opioids in their system. While methadone and buprenorphine have some potential for harmful ingestion, they are key elements that decrease harm for people who use opioids and help assist the shifting narratives toward treating substance use as a medical, public health concern.

Methadone and buprenorphine are both regulated drugs and the former is only accessible through rigid, high barrier, monitored, scarce, methadone clinics, unlike the latter which can be prescribed in offices and restrictions aren’t as tough. As mentioned by harm reductionist Shoshana Aronowitz in an article for Filter Magazine, the structure and regulations of the clinic she worked at made it so that the “ultimate purpose was not to promote patient health, but to police people who were prescribed a controlled substance mean tot “control” their addiction”. Many harm reductionists are actively demanding less restrictions on MAT rules and guidelines and luckily some changes had been made and restrictions have been lifted during the 2020 pandemic.

Harm reduction medicines, sites, and strategies have barriers, regulatory loops to jump through, and issues with police-state and public health surveillance. Despite all this, MAT can be a lifechanging (and lifesaving) component of reducing harm for PWUDs. It’s proven to be a safer alternative that reduces the harmful effects of opioid use. It’s also more cost effective and economically sound than imprisonment; according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, it has been estimated that the cost of methadone treatment averaged around $5,000 a year, compared to approximately $24,000 for State and Federal prisons to keep people confined proving that the criminal model is both inefficient and too expensive.

[More on Drug Policy Alliance: Methadone and Buprenorphine]

Please understand that the movement to medicalize harmful substance use and shifting conceptions about the humans that use drugs is written along racist and classist lines. The current manifestation of what has been coined as the “Opioid Epidemic” — which has gained national attention, federal funding, and Republican policymakers support — is positioned this way because it has been framed as a white problem. Historically, (and still prevalent today) when the population of afflicted drug users are Black (re: Crack Epidemic), they are criminalized, punished, and imprisoned rather than medicalized and treated with medical, health care related measures and state based social support. This is also seen along the criminalization of cannabis and Mexicans/Mexican-Americans and working class, poor, or rural white PWUD who are frequently left out of the picture. Media and representations of people use drugs create, replicate, and expose just how racialized drug use is and what kind of resources, treatment, and sympathy is called on. In a study of media coverage about white non-medical opioid users and black and brown heroin users from 2001-2011, how a population is represented in media “support policy responses that intensify the criminalization” or call for medicalization, according to the Drug Policy Alliance’s managing director Julie Netherland and anthropologist Helena Hansen. While there is motion for medicalization as indicated by the NIDA definition, studies, and more implementation of medicalized drug services and strategies, this shift does not evenly address racial and classed drug use or socio-political contributions to health.

The elimination of criminal penalties for drug-related possession, consumption, and sale has been a particularly hot topic during the 2020 general election. The harm reductionist stance recognizes that when drugs are criminalized that specific populations are being criminalized. The criminalization of people who use drugs was directly challenged on a massive level when voters in Oregon passed decriminalization of all drugs (measure 110) and voters in New Jersey, Montana, Mississippi, Arizona, and South Dakota (medical use) legalized marijuana. These new measures indicate a shifting conceptualization of PWUD and treatment in political, economic, public health, and mainstream public opinions.

Measure 110 spearheaded by Drug Policy Action, opposes and seeks to undo the decades of tough on crime policies and drug war violence that have harmed so many people — specifically Black and Brown communities. Cannabis tax revenue and funding saved from decreasing drug policing, jailing, and imprisonment will now go to treatment, other public health services, and social resources (like housing and harm reduction!) without raising taxes.

As the Drug Policy Alliance mentions, there are projections that this shift will result in a 95% decrease in racial disparities in drug arrests.

Just like needle exchanges and MAT, decriminalization does not encourage more drug use or crime — it reframes how drug is conceptualized and treated by meaningfully addressing the health and autonomy of the person using (rather than just violating, incarcerating, or otherwise harming them — or in many ways, letting them die).

Since 1971 when Richard Nixon declared the “War on Drugs”, implemented tough drug policies, expanded drug agencies (which all expanded under Ronald Reagan’s anti-drug campaigns) there are ten times more people behind bars for a drug law violation. This was not to punish drug use – it was to punish social movements (anti-war) and people (Black Americans) and that intel is recorded.

Policies related to the War on Drugs have drastically increased the number of people arrested, convicted, and incarcerated for drug-related crime. At the federal level, “people incarcerated on a drug conviction make up nearly half the prison population. At the state level, the number of people in prison for drug offenses has increased nine fold since 1980, although it has recently started to decline. Most are not high-level actors in the drug trade, and most have no prior criminal record for violent offenses” according to the Sentencing Project. Data from 2014 indicates that incarceration is not an effective drug control and prevention strategy – even in strictly economic terms there’s a high cost with low return. Not to mention all the lives, families, and communities that incarceration has disproportionately targeted, impacted, and disrupted.

The over-policing and over-incarceration of PWUD have led to 65% of the prison population with an active substance use disorder (SUD) and another 20% who do not meet the official SUD criteria but were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime.

Drug policy problematically targets and punishes users and sellers (which is a blurry, ineffective distinction) rather than addressing health or the conditions that produce drug use while disproportionately targeting and impacting Black and Latino people.

The lack of efficiency in decreasing crime and/or drug use with punitive measures proves that this system is (unsurprisingly) ineffective, but also focused on fueling the prison industrial complex, punishing rather than rehabilitating, and creating/maintaining a social order rather than combatting crime or helping PWUD. Decriminalization is vital to racial justice. Criminalization does not, and has never, improved lives at large — it ruins lives. Including the violence of policing, arrest, and incarceration, being criminalized marks people which “creates barriers that can trap people in a cycle of poverty and discrimination and lead to higher rates of chronic health issues and substance use disorders” according to the Drug Policy Alliance. So, the drug war and criminalization exacerbate — rather than alleviate — the conditions that fuel harmful substance use (like insufficient housing, poverty, resource poverty, lack of social systems, racism, etc.).

As Johnny Bailey, community outreach coordinator at HIPS, says about incarceration, “when has the legal system actually helped addicts? I know whenever people are like, ‘drugs will ruin your life’, a quarter of that, minimum, is the legal part of them ruining your life. And when people go in, you go in for a 10-year, a 10-year bit or something, and you’re not coming out to the ability to get a decent job, right? And in that 10 years, you could have done all sorts of things that are going to turn you around. No matter what you turn around in prison, you’re probably coming out to a world that’s hard.”

[More on understanding and dismantling the drug war can be found on Drug Policy Alliance website.]

Decriminalization of all drugs in Oregon, the growing number of states with marijuana decriminalization, more safe consumptions sites, and the change in federal funding that may now be used to purchase fentanyl test strips (FTS) indicate promising shifts in popular opinion about the societal understanding of drugs, mitigating harm, and shift towards health services rather than criminalization. As of October 2021, HIPS and the Drug Policy Alliance are spearheading a campaign, #DecrimPovertyDC with a coalition of over 40+ groups to “decriminalize drug use and possession, and instead address collateral consequences of drug convictions and invest in evidence-based public health approaches that dignify and support people who use drugs” according to the campaigns website.

Harm reduction is about health not violence. autonomy over coercion. compassion over judgment.

To Recap: Harm reductionists and harm reduction centered policy is grounded in health over violence; autonomy over coercion; compassion over judgment. The effects from drug use exist on a spectrum and affect everyone differently. Structural violence, systemic inequality, and punitive, prohibitionist policies exacerbate the harms from drug use. Harm reduction is about health, care, and community not prohibition, criminalization, and narrow ideas about “recovery”.

So here we are in the U.S. — a wave of pharmaceutical prescriptions led to an overdose epidemic in the 1990s and the rise opioid related overdose death toll keeps rising. In 2017, The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency for the opioid overdose epidemic and crisis. The national outcry, political intervention, and medicalized responses are mostly because the epidemic is disproportionately affecting white people whereas when Black communities were suffering from the crack epidemic in the 1980s they were politically and societally criminalized, ostracized, and left to die.

As Joe Biden, has taken office as President of the United States, you may have heard about his son Hunter who struggled with harmful drug consumption (including alcohol) and went to several drug treatment centers throughout his life. It was inspiring to see Joe Biden declare, “I’m proud of my son” in the presidential debates with Donald Trump in 2020 when the latter slandered Hunter’s struggle with drug use. It’s great to see President Biden accept his son and directly combat the pervasive and present stigma around drug use espoused by Trump, but it’s hard to ignore that while Hunter was afforded treatment opportunities and employability due to his privileged position in society that so many others are further victimized, incarcerated, and harmed for their drug use. And this symbolic exclusive gesture Biden pardoned his son with is suspect when he has a history of writing tough on crime bills that are pro-drug criminalization that have fueled racial incarceration disparities.

Drug use impacts everyone. But not all people are afforded the same access to treatment, treatment development, and treatment options.

With this administration, the toxic drug supply, and the exacerbating effects of COVID-19 that’s creating the highest overdose death toll in a 12-month period, new drug legislature and action is vital. As of November of 2021, over 100,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in a 12-month period. In response to the growing public health crisis, this year federal funding was released to support fentanyl testing strips and federal harm reduction funding.

While harm reduction becomes a more viable set of strategies for the public health sphere it has been subjected to the problem many radical social movements face in the process of legitimization – cooptation and settling for reform. Shane Sullivan, a harm reduction outreach worker, mentions, “when government bodies use the term [harm reduction] it is always really concerning” and discussed how the government focuses on the harm reduction “program” rather than radical social change (which is unlikely to occur from within the current state apparatuses).

When programs are the talking point and main course of action, attention is diverted from drug-related harm that is driven by criminalization and the tainted drug supply. More is at stake of being lost when, “people who use drugs are centered first and foremost historically and that will get lost more and more as it gets more mainstream”, says Shane. They echoed the concern that an overly biomedicalized, apolitical, institutionalized, reformist harm reduction stance that loses drug-user leadership and community organizing will obscure and co-opt the more radical harm reduction agenda that includes ending the criminalization and stigmatization of PWUD that would stop the mass production of death, poverty, insecurity, and harmful substance use.

The harm reduction movement must remember, and in some cases learn about, the radical roots of this practice, philosophy, and movement. With an ideology and philosophy based on health, wellness, autonomy, and reducing harm affiliating with drug use with the understanding that socio-political factors influence and increase who is at risk, harm reductionists can cultivate a backbone to address harmful substance use on multiple levels that is creative, fluid, and radical that can cultivate liberating tools, strategies, and actions. If it is reduced to a few sets of practices

or programs and loses the philosophy or affiliation with a radical social movement that addresses the failures and violence perpetuated by the state, then the tools and strategies themselves may continue to produce harm rather than alleviate it.

Options, autonomy, and advocating for better drug-related systems are a few reasons why harm reduction is so important. Harm reduction considers everyone and doesn’t force a “one size fits all” philosophy. Adopting this stance and using its practices also directly acknowledges that not all people necessarily wish to fully abstain from drugs. This model acknowledges, normalizes, and addresses people by meeting them where they’re at — by accepting that drug use may be a part of a person’s life and to equip them with the best resources and options for them to decide what they wish to do and, in some cases, to make any positive change they wish to strive toward. There is an openness and fluidity to addressing community needs the harm reduction way that is not always reflected traditionally in drug rehabs, 12-step fellowships, and Therapeutic Community (TC) models that push abstinence and more narrow conceptions about drug use and recovery.

And to further compare between those models and harm reduction at large, in the latter harmful substance use isn’t reduced to merely biomedical terms (brain disorder, genetics, mental illness, disease) or spiritual ones (like in AA, NA, and church groups). Social, medical, and structural influences are acknowledged and addressed. So many factors contribute to why any person uses drugs while a plethora of reasons contribute to drug use that is spiritually, physically, mentally, or socially problematic (or helpful, meaningful, and sustainable!).

Policy, institutions, societal fearmongering, and misinformed (incorrect) drug education has led to narrow ideas about what problematic drug use is, reductive and inhumane assumptions about PWUD, and oversimplified punitive measures to address it with few other models of care to utilize. We need to rethink drugs on a societal level and work for harm reductionist and decriminalization models. Decriminalization does more than decriminalize drugs — it decriminalizes people.

Plus, drugs are less inherently harmful than many people in America may have been raised to believe. Under the law, the harm that any drug can cause becomes even more arbitrary and is classified to penalize, punish, and police people rather than protect them. The line between medicinal and problematic or illegal is constantly shifting

Formed in 1993 by community representatives, HIPS (Honoring Individual Power & Strength) initially mobilized around youth sex worker outreach and counseling in the District. They have since expanded programming to address to following: HIV/AIDS education, testing, and resources; peer education programming; drug use safety, education, and substance use treatment; overdose prevention services; syringe exchange; programs specifically for LGBT+ sex workers and safety; counseling; educational and training services; housing services; virtual medical appointments; and more.

Formed in 1993 by community representatives, HIPS (Honoring Individual Power & Strength) initially mobilized around youth sex worker outreach and counseling in the District. They have since expanded programming to address to following: HIV/AIDS education, testing, and resources; peer education programming; drug use safety, education, and substance use treatment; overdose prevention services; syringe exchange; programs specifically for LGBT+ sex workers and safety; counseling; educational and training services; housing services; virtual medical appointments; and more.

HIPS’ brick and mortar drop-in center is located on 906 H street NE. They also provide mobile supply and medical services on their outreach van and a 24-hour crisis hotline. As mentioned by outreach staff, HIPS develops as the community needs them. If there is a demand or a need, they do their best to add it under their umbrella (demonstrating their commitment to the communities).

In addition to providing these vital resources, services, and training to sex workers, the LGBTQ+ community, and PWUD in the District, HIPS is active in policy and advocating for the rights of drug users, sex workers, and trans people. In 2020 HIPS and the Drug Policy Alliance jointly submitted a letter to DC Council for the removal of criminal penalties for the possession or distribution of what’s been deemed “drug paraphernalia”. In November, the Opioid Overdose Treatment and Prevention Omnibus Amendment Act of 2020 was unanimously advanced (although it still awaits to be effective as law). This decriminalization is a strong step forward for public health, harm reduction services, PWUD, and racial justice in the district.

On the tail end of this win, in 2021, the Drug Policy Alliance and HIPS organized a coalition of 40+ organizations and teamed up again to launch the campaign #DecrimPovertyDC. The mission is, “through ongoing advocacy, we aim to replace carceral systems with harm reduction-oriented systems of care that promote the dignity, autonomy, and health of people who use drugs, sex workers, and other criminalized populations.” Learn more about the movement and get involved here!

Amidst the worldwide pandemic in 2020 that exacerbated existing inequalities and health concerns, the clinical services team cured 154 people diagnosed with Hepatitis-C, started to provide gender affirming hormone therapy, and distributed 550,000 sterile syringes (272,000 more than 2019), and distributed 12,459 naloxone kits (more than doubled from 2019).

[You can find all of HIPS policy recommendations here.]

HIPS advances the health rights and dignity, of people and communities impacted by sex work and drug use by providing non-judgmental harm reduction services, advocacy, and community engagement led by those with lived experience."

HIPS' Mission Statement

A core part of this project in collaboration with HIPS seeks to highlight and raise awareness about harm reduction as both a philosophy and practical set of tools — centering on the core belief that people who use drugs are human beings that deserve better access, options, and autonomy to make decisions about their own health and wellness through. We did so through collaborating on a series of community conversations and overdose opioid reversal trainings with HIPS in different wards from May 2021 to August 2022. Free meals, free training and Narcan, creative community collaboration, and oral history stations were featured. Some events were in gardens, some included seeds and herbal medicines, others featured panels, and all of them had great tunes and conversations.

Ward Four | May 15, 2021

On May 15th, 2021, the Humanities Truck, HIPS, and Ward Four Mutual Aid teamed up for our first event — we provided free meals, opioid and drug education, and opioid overdose prevention training at Mosaic Church of the Nazarene where supplies are distributed weekly by Ward Four Mutual Aid. Shortnee Street Eatz catered and provided a delicious array of food that left many people with full, satisfied bellies. In addition to training, free food, and great conversations we will also be gathering testimonials and interviews from people with lived experiences with drug use to explore harm reduction as a movement, philosophy, and practice at future events.

Since HIPS is a harm reduction organization it follows that their drug education embodies that philosophy rather than a strictly abstinence based, moral, or punitive model. They emphasized that drug use exists on a spectrum —drugs and use affect every person differently. The role and goal of harm reduction isn’t to fearmonger about the dangers of drugs or judge people for their drug consumption or lifestyle. Harm reduction’s purpose, as shown via the training, is to educate about some risks affiliated with drug use, accept (rather than deny or punish) that drug use exists and will continue to exist, and to entirely center on how to reduce harm. This reduction of harm can take many forms like testing personal drug supplies, challenging racist drug-policies, or carrying and/or using naloxone.

The training had many attendees who were fixated on and engaged with the training. We addressed opioid use specific to the district, the core principles and some myths about harm reduction, and how to reverse opioid overdoses. Several people sparked great conversations and asked clarifying questions. At one moment, a man had a lightbulb moment about harm reduction when he acknowledged that it isn’t about enabling drug use, but about learning ways to navigate the risks and reducing the harms affiliated with drugs. The idea that harm reduction enables drug use is a common misconception, but the man participating in the training saw through it and saw it as a safety measure instead.

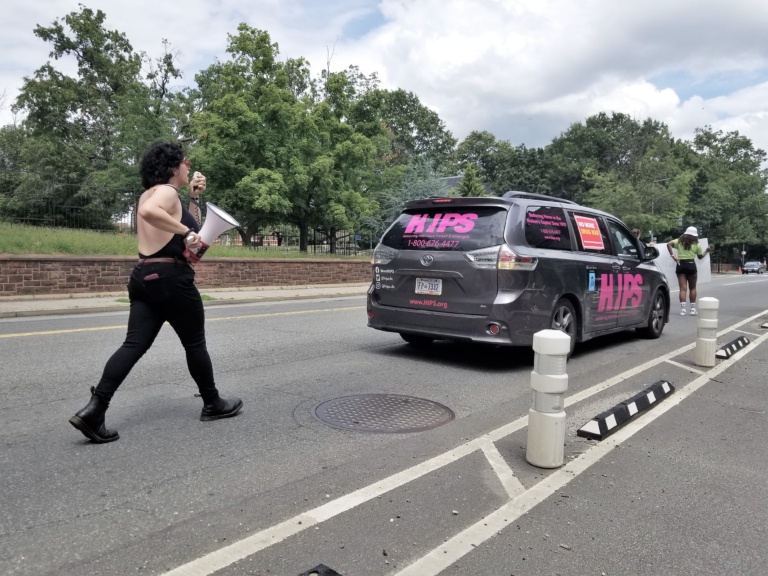

Support, Don't Punish Rally | June 26, 2021

Video of Jessica Martinez, methamphetamine specialist at HIPS and organizer of the DC rally for Support, Don’t Punish. 2021. Video by Laura Sislen.

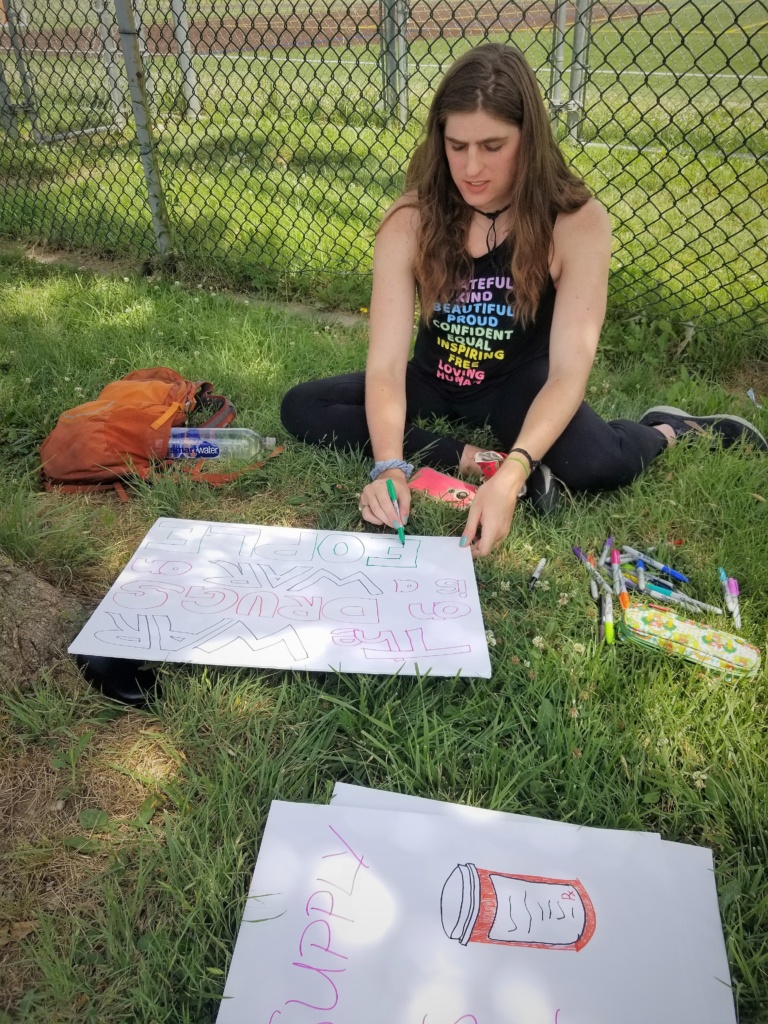

On June 26, 2021 HIPS and the Drug Policy Alliance, funded by the Levinson Foundation, marched in solidarity with the campaign “Support, Don’t Punish” calling on DC residents and policymakers to choose care over violence when it comes to people who use drugs. This march gathered around 1:30 on a hot and humid day near Union Market in DC and made posters with harm reduction and decriminalization slogans like “safe supply saves lives”,”Decrim Now!”, and “invest in public health”.

We marched from 2:15 at Union Station (Brentwood park on 6th) to Freedom Plaza — 72 minutes of chanting, marching, and dancing. We were fiercely led by Jessica M. on the megaphone and Alexander/a B. and Queen A. with a banner that read “be nice to drug users; #DecrimNow; a war on drugs is a war on us; HIPS logo” in bold black and pink lettering.

Exhilarating marching led to high spirits as Jessica led the group with the rally cries, “DECRIM! NOW!”, “hey hey, ho ho, racist drug wars got to go”, “a war on drugs is a war on us” and the demand that “all personal use substances are decriminalized for all residents of the District” since we have “antiquated drug laws” while “we need health professionals not police, not jail”. A firm reminder that “every overdose is a policy failure”.

When we arrived at Freedom Plaza we were ecstatic and pumped. No cops, no agitated drivers, we kept the group together, and had a very positive response from the people of DC.

At 4:00 pm testimonials were shared about experiences with the harms and violence perpetrated by the war on drugs. Folks talked about not being able to seek medical care because of racism and stigma. It was repeated frequently that the war on drugs is not a war on drugs, but a war on people that disproportionately targets Black and Brown people. Tamika Spellman, policy and advocacy at HIPS, demanded change and that we must introduce a new way of thinking, remove barriers to resources, and redirect funding to housing, jobs, and not jail. As Michaelisa, a peer educator with HIPS, openly shared her testimonial she elaborated on the violence and harm caused by the drug war with her experiences being jailed in the wrong jail as a trans woman and the cycle of incarceration and toxic environments that lead to harmful and risky drug use. Stigma, punishment, incarceration — it must end and be replaced with housing, health care, community, systems accountability, empathy, and support. A reminder that harmful drug use is a public health concern, not a carceral one.

Ward 6 | July 12, 2021

On July 12, 2021 HIPS and Truck fellow Laura Sislen collaborated with Deeds of Kindness, a non-profit community based organization that offer peer services, essentials (clothes, shoes, PPE, toiletries, men and women’s apparel, and grab and go food), and Kita Marie’s Kitchen at First tabernacle Beth-El (401 New York Ave. NW) for the second Community Collaboration.

During the event planning stages, Johnny (from HIPS) and I met with Elleecia Washington from Deeds of Kindness. HIPS, particularly the late and great Moe Abbey and renowned DC harm reductionist and drug user advocate, has partnered with the group before and were glad to collaborate again. During our conversation Elleecia heavily emphasize the importance of community and building trust. This spurred a small conversation about the community building efforts that groups like HIPS and Deeds of Kindness embody and how that is why their outreach is meaningful to community members. Without the trust there is no outreach.

In total more than 20+ folks either stopped by for (delicious) food and resources or stayed for the entire training. With a smaller turnout we were able to have a powerful and engaging conversation about drug use, lived experience, and opioid overdose prevention When the spirit of the community conversation is more communal it allows the attendees to shape the dialogue more We spent some time discussing the trauma, fear, and intensity of experiencing or witnessing an overdose and the different responses the body has to overdosing on different drugs. Someone asked, “do bystanders actually do it?” in reference to provided naloxone to an overdosing person in which we talked about the importance of being trained and shared stories about the intimidation of administering naloxone.

Another topic that interested a few attendees was how the COVID-19 pandemic affected drug use and overdose. It’s gotten significantly worse with the conditions that the pandemic exacerbated. The virus impacted the drug supply, drug trade, and amplified isolation — which all lead to dangerous drug supply and more drug use risk. At this point, more than 90% of street heroin is fentanyl, “it’s ridiculous” one attendee mentions.

Ellecia joined the conversation and talked more about the importance of trust. People use drugs for so many reasons. The people are in pain (for a variety of reasons) and the only way to really help anyone s to “meet people where they at” and “figure it out together” since “money and bureaucracy keep people stuck” mentions Elleecia. “We must engage each other” she states echoing the sentiments of the harm reduction philosophy that if the people most impacted are not looking out for each other and pushing institutions for change and supporting each other’s health then no one will. One of her last remarks was that “your brand is how you treat people” in which Alex Bradley who was leading the training added that that’s HIPS’ model. It’s about building relationships not really about volunteering. When the pandemic hit groups like HIPS, Deeds of Kindness, and mutual aid groups mobilized around the “shut down” and “figured it out”, mentions someone at the conversation. We all expressed our frustrations and disappointment with how the pandemic has led to less change about the deep inequalities and injustices embedded in the United States that were exacerbated and exposed to those who were privileged enough to not see it before a global pandemic. In spite of this and for each other, we mobilize amongst ourselves and we build community and we build trust.

Ward 1 | July 24, 2021

This time HIPS and the Humanities Truck collaborated with DC Ward 1 Mutual Aid, Revise Inc., ACLU of DC, and Stop Police Terror Project DC at Temperance Alley where we tabled, shared community info, ate Ben’s Chili Bowl, told stories of recovery, gathered for overdose reversal training and resource distribution, and had plenty of fun to fill our cups.

Temperance Alley is an abandoned community garden behind 1909 13th street. Mutual aid and local groups have reclaimed this space, this space that is technically owned by developers who will erect a 105-foot hotel and apartment complex. These plans are not until 2023 so in the meantime community members are using the space as a park, community garden, and outdoor classroom “designed by neighbors, for neighbors” where they do park beautification, meditations, storytelling, lawn games, yoga, and so much more.

This exhibit will be continuously updated to reflect some notable developments in policy, gathered oral histories, testimonials and interviews, and other information that fits. These updates, as well as when the web-exhibit becomes static, will be noted.

Questions about the exhibit or harm reduction? E-mail grad fellow, Laura S. —LJsislen (@) gmail.com

First posted 5/13/2021. Updated 10/27/2021. Updated 12/9/2021. Updated 7/21/2022.